John Keats’ Final Voyage narrates the last six months of the poet’s life using the virtual map Google Earth. The story is especially close to the hearts of everyone associated with Keats-Shelley House; it is in essence the story of the museum. 200 years after Keats’ departure from England in September 1820 seemed the perfect moment to remember the reasons for the journey, its privations and pathos, its landscapes and seascapes, its understated heroism and its aftermath. The bicentenary also offered a chance to review the role the Final Voyage has played in Keats’ biography, its mysteries and gaps, and the gauntlet it throws down to biographers and scholars.

The Final Voyage is in effect not one Final Voyage but three.

- Part one recounts Keats’ sea passage from London to Naples in September and October 1820 – which began his Hail Mary bid to rescue his health from consumption: ‘chapters’ 1–113.

- Part two comprises the 10-day quarantine in Naples, Keats’ brief respite in the city and the road trip to Rome: chapters 114–227.

- The third and last part maps a more metaphorical final voyage: Keats’ slow, anguished decline at 26 Piazza di Spagna in the first months of 1821, and his death on 23rd February: chapters 228–316.

These three main sections have sub-sections of their own: including background to Keats’ illness, the mythical writing of Keats’ ‘final’ poem, ‘Bright Star’, and a brief history of quarantine and plagues in Naples.

Final Voyage User’s Guide

To open the map, click: https://bit.ly/JohnKeatsFinalVoyage

Google Earth can take a few seconds, so have a cup of tea at hand. I find the page often needs to be visible on your screen to open successfully.

Set your browser to 100%: CTRL +/- on the keyboard shortcut. You can use this shortcut to zoom in and out on the text, but this will also alter the dimensions of the map.

To navigate through the map, use the grey dialogue box in the bottom left-hand corner. The arrows < > allow you to move forwards and backwards through the posts.

Clicking ‘Table of Contents’ opens all the visible posts, which can be opened with another click.

Map Views. Each post is interactive. You can change your view using the icons in the bottom right-hand corner: zoom in and out (-+), move around the neighbourhood (<>), or shift between 2D and 3D. Enter street view by turning the figure icon gold, and then click on any of the blue lines to hit street level. The compass always you to swivel your view even faster.

Text Box. The image at the header of each post can contain more than one picture or video: scroll through using the arrows. To increase the font size, use CTRL +/- on the keyboard shortcut. Remember, this will alter the view of the map’s design.

Links in the text are highlighted in blue. These can direct you to resources outside Google Earth (e.g. the paintings used in image box) or to ‘Hidden Posts’ in the map. These often contain full texts of letters, alternative views of a scene, and sometimes subplots to the central story: the Shelleys in Pisa, Charles Brown racing from Scotland to meet Keats, or the one-year anniversary of Keats writing To Autumn in Winchester.

To return from a ‘Hidden Post’ to the main narrative, click the link at the bottom of the post: Back to the Final Voyage.

Background

John Keats’ Final Voyage began life in September 2020. The initial plan was to use Google Earth as a way to commemorate the bicentenary of Keats’ voyage passage on the Maria Crowther from London to Naples, and then by road on to Rome. Giuseppe Albano, the curator at Keats-Shelley House then asked if I would keep the map going all the way until Keats’ death on 23rd February 1821.

This provided a challenge of its own – except for the first few weeks in Rome, Keats hardly moved from 26 Piazza di Spagna, which would mean any number of pins crammed onto the Spanish Steps. But even here I realized, there were voyages of a sort: see Keats’ short lived walking tours around the Pincio, or the melancholy final ‘final voyage’ as his body was transported across Rome from Piazza di Spagna to the Non-Catholic Cemetery.

It didn’t take long for the initial ambition to expand. The text box allowed me to supplement the basic task of pinpointing where on (Google) earth Keats was each day with narrative, images, audio and video. The viewer, I realized, could travel not only in space but time – to mark the anniversary of To Autumn, to follow Rupert Brooke and also Thomas Hardy’s Keatsian adventures on Lulworth Cove.

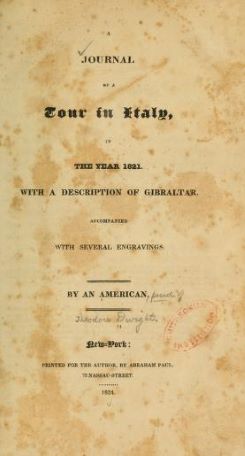

For the story itself, I relied largely on Joseph Severn’s accounts, supported by Keats’ few letters and one or two other contemporary sightings: for example, Charles Macfarlane’s short memoir of meeting Keats in Naples. My biggest debt of thanks has been to Grant Scott’s invaluable edition of Severn’s letters and prose writing. When I began to proof and polish the first version of the Final Voyage, I found added help from Theodore Dwight’s travel diary describing his journey from America to Rome, via Naples, only weeks after Keats. On the day Keats died in Piazza di Spagna, Dwight visited the Non-Catholic Cemetery, a coincidence I found at once strange and emotional.

The challenges posed by the story (its gaps, inconsistencies and mysteries) have also brought home the brilliance of the many accounts of this final act in Keats’ life. While Scott alerted me to the errors in William Sharp’s influential account of the Final Voyage, his biography of Joseph Severn has nevertheless been an important guide. The same goes for Sheila Birkenhead’s vivid, almost novelistic lives of the painter. Of Keats’ biographers, I have found myself reaching most often for the accounts by Nicholas Roe, Robert Gittings, and Amy Lowell. A conversation with Nicholas Stanley-Price about Keats’ funeral and grave inspired me to map the route of this melancholy ‘final voyage’. You can hear the result on the Keats-Shelley Podcast - below.

New Findings: Maria Cotterell

John Keats’ Final Voyage has been a labour of love, by turns moving, frustrating, inspiring and frequently obsessive. Almost 10 months in the making, the 316 posts totals something like 90,000 words. I have spent long hours chasing all manner of sub-plots, sidetracks and red herrings down allmanner of blind alleys. I have researched 19th century vetturas, wondered how long it took to sail from Dundee to London, tried to discover who might, or might not, have attended Keats’ funeral, failed to find where Dr Clark worked in Rome, the history of disease and plague in Naples.

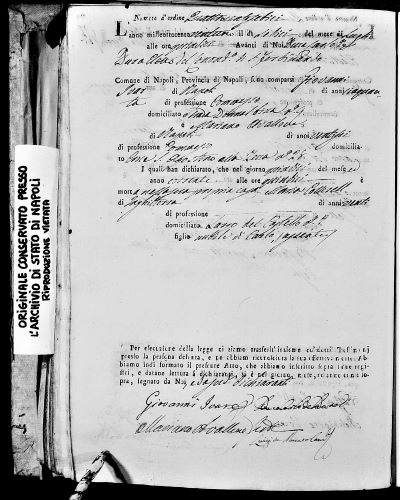

One of these investigations concerned the two passengers who sailed alongside Keats and Severn on the Maria Crowther. While Mrs Pidgeon seems to have vanished from recorded history, I did find some new traces of Miss Cotterell, the young woman who like Keats was travelling in a desperate bid to save her life.

You can read more about these discoveries, about Miss Cotterell’s story and the Final Voyage map itself in an essay in the Bicentenary issue of the Keats-Shelley Review. Listen to an audio version of the essay on the Keats-Shelley Podcast: embedded above.

As I wrote there, the three new facts were ultimately less important than the imaginative journey that accompanied the research. If it wasn’t for the Final Voyage, I doubt I would have paid Miss Cotterell a second thought. Thanks to the Final Voyage, I found myself thinking about her brief life, and empathizing with her courage in ways I would never have done otherwise.

The same applies to both Keats and Severn. I would never claim to have the first idea what each man went through during those five months. Nevertheless, the discipline of re-tracing their journeys, day by day, at least pushed me to consider their suffering and their dignity, their flaws and their friendship in ways I had never done before. This often eerie experience has been made all the eerier by melancholy echoes in our own time: the Covid-19 pandemic and the weird seclusions of 2020’s lockdowns.

The Final Voyage will continue to be updated, tidied, refined and corrected. All mistakes are my responsibility. I will also seek to obtain any necessary permissions for images. If you spot errors (in text or fact), or want to comment, or ask a question, please email me: ajskidd@gmail.com

James Kidd