Each Chair of the Keats-Shelley Prize Judges is asked to deliver the annual Keats-Shelley talk, in addition to judging the poetry and essay prizes and announcing the winning entries. On 29th April, 2019's Chair, Professor Michael Rosen took as his subject the strange and secretive publishing history of PB Shelley's 1811 pamphlet, A Poetical Essay. Enormous thanks to Michael for a quite brilliant performance, and for providing the text, whose flavour we have attempted to catch if not match. The talk was first published in The Keats-Shelley Review.

For details of 2020's Keats-Shelley Prizes click here.

Michael Rosen, pre-speech with KS Poetry Judges Deryn Rees-Jones and Will Kemp, and also the enigmatic K-S Twitter

Thanks very much indeed to Keats-Shelley Memorial Association for inviting me to be the final judge for this year’s competitions and indeed for hosting this lovely event. Special mention to all the finalists in the competitions - essays and poems. Remarkable standard. I enjoyed them all very much indeed.

For this little talk let me first take you back to November 2015.

For nine years, the world of scholarship and those interested in the works of Shelley had been put in a very strange position.

In this period of time, (nine years), we had known that a work by Shelley (that had been described for a long time as ‘lost’), had been found. Let’s think about that for a moment. What do those words mean: ‘lost‘ and ‘had been found?’ More on that in a moment.

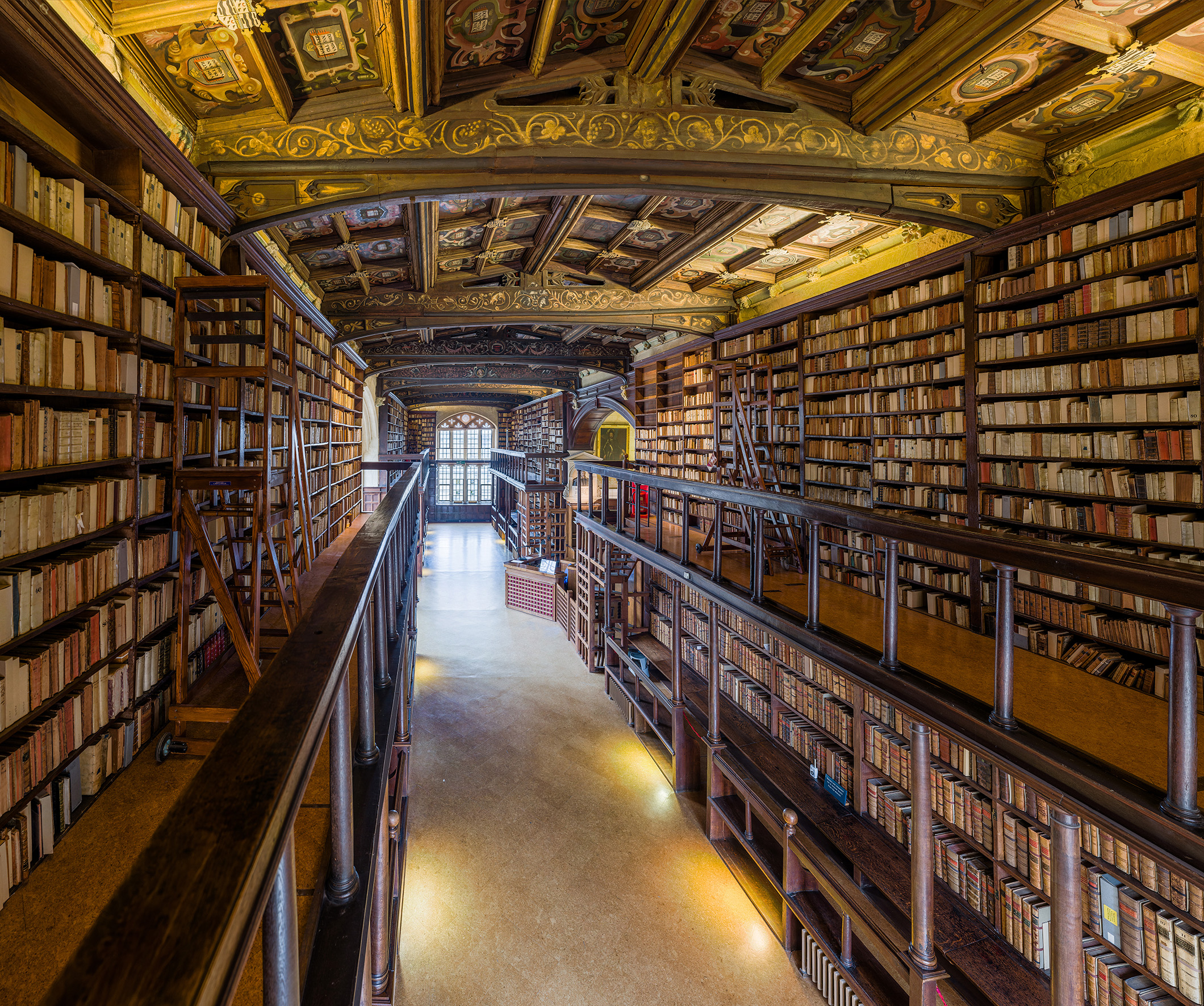

What had happened was that in 2006 the scholar H.R. Woudhuysen announced in an article in the Times Literary Supplement that Shelley’s poem ‘A Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things’ had been ‘re-discovered’ .

‘Re-discovered’ from where? From when?

The ‘when’ question is easy to answer: from 1811.

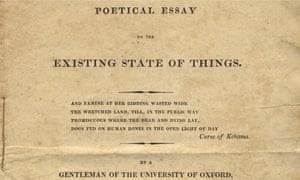

On March 9 1811 a poem, ‘Poetical Essay’, was advertised in the ‘Oxford University and City Herald’.

It was published by, but not in, this newspaper, as a 20 page pamphlet, written by a ‘gentleman of the University of Oxford’. This was in fact Percy Bysshe Shelley then aged 18 in his second term at University College.

It’s not known for certain how many copies were printed or how many sold other than that they seem to have all disappeared - bar one. This single copy seems to have been the one that Shelley gave to his cousin Pilfold Medwin who took it to Italy.

Notice my use of the word ‘seems’. Anything in the murky world of the history of manuscripts and lone single editions has to use words like ‘seems’.

(Digression - anyone interested in this world should spend some time looking at the fates of the manuscripts of John Clare, Franz Kafka and James Joyce.)

Let’s come forward again to November 2015.

For nine years, this poem had only been seen in full, only been allowed to be seen by a tiny group of people. The only person to have both seen it and written about it at any length was H.R. Woudhuysen in an article in the Times Literary Supplement in July 2006.

So where had it been for these nine years?

We’ll come to that in a moment.

How about in the period between 1811 and 2006?

According to the Bodleian Library, the poem wasn’t officially identified as being by Shelley till 1872. It was at this time that two nineteenth century scholars talked of: ‘valuable information as to the library wherein a copy of Shelley’s Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things is affirmed to exist’ - yet neither of them or anyone else at the time thought the matter was worth pursuing.

A ‘library’ - what does that mean? What kind of library?

And why didn’t anyone pursue the matter in the 1870s? (I don’t have the answer to that question.)

The poem itself is highly political - both in what it says and in its purpose. The purpose was to raise funds on behalf of a journalist called Peter Finnerty. Here’s Woudhuysen: "Finnerty’s reports on these events [that is, the conditions facing troops in wars against Napoleon] in the Morning Chronicle led to his arrest and transportation back to England. In January 1810 he accused Lord Castlereagh of trying to silence him and compounded the offence by repeating accusations against the politician about the abuse of United Irish prisoners in 1798.

Finnerty was tried for libel in February 1811 and sentenced to eighteen months in Lincoln Gaol. It was not the first time he had gone to prison as a result of clashing with Castlereagh: he had previously spent two years in prison in Dublin for printing a seditious libel and had been made to stand in the pillory. This second libel case was reported in great detail and Finnerty’s plight attracted widespread support, prompting a debate during the summer in the House of Commons and a public subscription, initiated by Sir Francis Burdett, which reached Pounds 2,000 on his release. Among those who contributed to a fund to maintain the journalist while he was still in prison was Percy Bysshe Shelley, then an undergraduate at Oxford in his second term at University College. His name appears in a list of four subscribers, each pledging a guinea, printed in the Oxford University and City Herald on March 2, 1811"

The poem itself in the words of Professor John Mullan is: 'A verse denunciation of oppression in the colonies and corruption at home...”

Nevertheless, it had been lost. Well, if you think about it, not exactly ‘lost’. More ‘out of sight’ for nearly everyone.

But where had it been?

How was it out of sight?

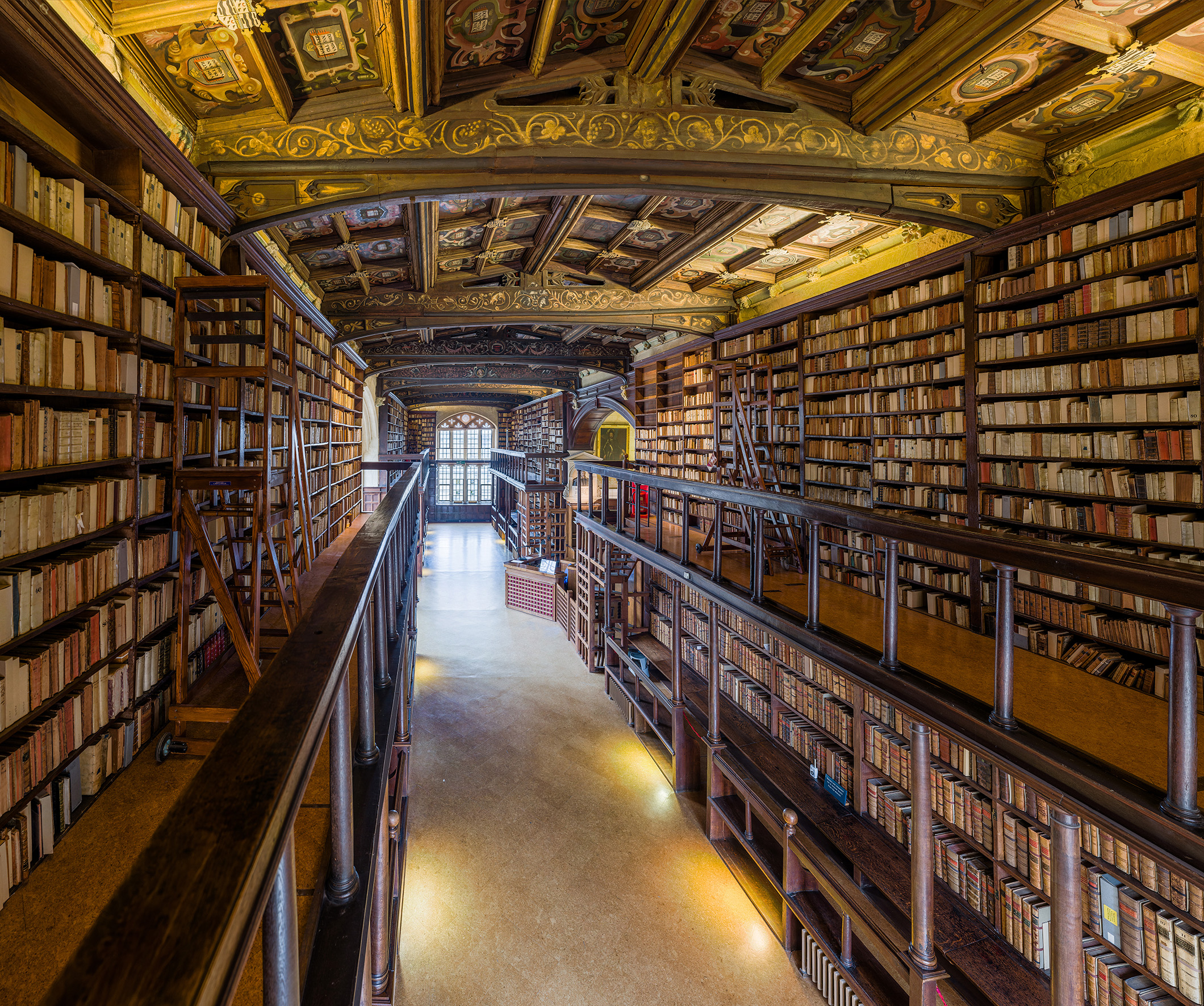

All we have is this image of an unnamed ‘library’...

But, we’re a gathering here tonight, interested in Romanticism, so let’s feel free to run our gothic or romantic imaginations over this story: all through the nineteenth and early 20th century, most copies of this 20-page pamphlet have ended up being used to start fires, tipped into rubbish bins....bar one. And this sits in a library...where is this library?...a country house perhaps? ...You’ve seen these, I’m sure. As we stroll through them, we see shelves rising from floor to ceiling, behind glass doors, jam-packed full of ancient books. Let’s make this country house a bit mouldering, a bit Castle Rackrent.

The pamphlet, we might imagine, is where? Tucked between two other books: nothing to do with Shelley - one is, let’s say, Grantham’s ‘Voyages to the South Seas’ (1758) (I’ve made that up) and a book I heard mentioned on Radio 4‘s ‘In Our Time’ on ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ the other day: an Elizabethan book on the interpretation of dreams. (I haven’t made that up. Really.) This stately home we’re imagining now has a catalogue of all the books and pamphlets but this pamphlet is only listed as, let’s say, (‘Poetical Essay’ 1811 Anon.). No one out of whoever lives in the house or who visits this house thinks a publication with a title as dull as ‘Poetical Essay’ is worth pulling off the shelves.

Come forward to the 21st century.

The mansion and the shelves are getting damp. Money is short for the aristocratic owners of the mouldering mansion, it’s time to bring in a valuer to see whether funds can be raised.

At which point enter one Bernard Quaritch. Based on that name alone, perhaps switch here from Gothic-Romantic to Dickensian.

Let’s imagine old Bernard Quaritch invited into the country home (inhabited by Miss Havisham of course). As Quaritch is poring over the old damp books, he suddenly finds the ‘Poetical Essay’. It is now in the hands of Bernard Quaritch, the ‘antiquarian booksellers’ of South Audley Street, London, W1.

We know this because it was announced in July 2006 that Quaritch had put up for sale what seemed then to be the sole example of the ‘Poetical Essay’, the sole source for the poem.

Again, let our imaginations run free - note the Romantic image there - of something called ‘the imagination’ that has a capacity - free of the mind or reason, to ‘run free’... taking us...where? Adark, musty bookshop, stacked up with books, thousands of them, with slips tucked in and protruding, men in dark overalls with pencils tucked behind their ears, moving silently about, one lone woman at a cash register reading one of the books herself? Old Quaritch is upstairs, dozing, an open bottle of port on his desk in front of him.

In actual fact, this is miles from the truth, because Quaritch say on their website: “We have been buying and selling rare books and manuscripts since 1847. Our founder, Bernard Quaritch, was born in 1819 at Worbis, a small town near Göttingen in Germany. After working for booksellers in Nordhausen and Berlin, he set off for London in 1842, aged 23.”

“On his death in 1899 The Times wrote “It would scarcely be rash to say that Quaritch was the greatest bookseller who ever lived.”

Quaritch is: “....now owned by book collector and investor John Koh.”

Switch image - let the imagination run free again - smart, shiny, immaculate office, every book carefully shelved, brushed, polished. Moving swiftly and purposefully around the offices are: smart, suited, recent Oxbridge graduates equally distributed women, men, culturally diverse, trans, and John Koh...who bears a remarkable resemblance to George Clooney.

It’s July 2006. The phone rings.

It’s Michael Rosen.

Michael says that he has read the article in the ‘Times Literary Supplement’ and asks if Bernard Quaritch - (at this point Michael still thinks that Quaritch is alive and well and living in South Audley Street) - will be making the ‘Poetical Essay’ available. Michael mutters confusedly about how easy it is to make digital copies these days, saying how the British Library was at this very moment digitizing swathes of their collection on line. In fact, he was at the library talking to a curator at the very moment they were working on the ‘Beowulf’ manuscript...Michael’s voice tails away.

No, says the person on the phone, the ‘Poetical Essay’ is not available to the general public to see and it’s not going to be digitized until a buyer is found.

The conversation gets awkward. Michael is asked if he wants to view the copy but he thinks that would be dishonest because he can’t imagine for a moment that he has the money to buy it. And anyway that’s beside the point. The point is, surely, that Shelley enthusiasts - (and the world )- should be able to read the poem. Who - after all - (asks Michael rhetorically), does literature belong to?

Bernard (or whoever it is on the end of the phone) politely points out that digitizing the poem isn’t going to happen.

Cut to Michael in his own work space. Think now, more BBC 4 profile...(I’m making this up too. More imagination. ) Alan Yentob is dawdling round Rosen’s books and picks up a 1954 copy of the Communist ‘Daily Worker’s’ Christmas Annual for children. He flicks the pages and finds a story...written by Michael aged seven.

‘Is this...?’ Yentob says

‘Hang on, Al,’ interrupts Michael, ‘don’t you see? They think they can own Shelley. It’s the capitalist paradigm. Purely because history has determined that there is only one copy of this poem, this copy has value. Because it has value, it becomes private property. Because it is private property, it can be withheld from view. But why, Alan, why?

‘Yes, Mike, why?’ says Alan.

Close up to Michael

‘In order to raise its price in the market place!’ says Michael as if he thinks he has discovered the meaning of life.

‘Yes,’ says Alan slowly - as is his wont - ‘but do we know if the poem is any good?’

Michael is waving his arms about and his eyes are popping.

‘That’s beside the point, Al.’

‘What is the point, Mike?’

‘The point is that literature belongs to all of us. And come on! How ironic that Shelley - yes, Revolutionary Shelley of all people - should be hidden from us so that the price of his words can increase!’

Cut to Michael walking past Alexandra Palace, in Muswell Hill.

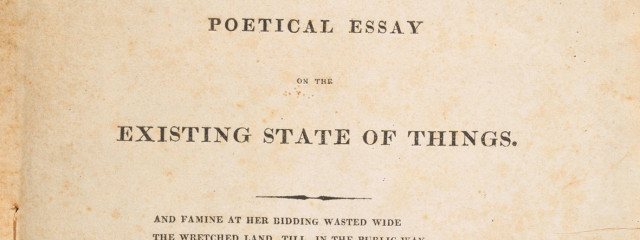

Michael stops to look out over London. We hear Jeremy Irons as voice-over saying, ‘Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair...’

(This gave the impression to viewers at the time that Michael thought he had built Alexandra Palace but perhaps it was ironic in a post-modern sort of a way.)

Back to reality: between 2006 and 2015, Michael (this bit is true - no imagination involved) writes letters to the ‘Times Literary Supplement’ and the ‘Guardian’, and writes articles on his blog about...why is Shelley’s poem not available, and - why aren’t Shelley scholars causing a fuss? Rosen claims contentiously that Woudhuysen’s scholarly article has in fact served the purpose of raising the value of the object (not the poem itself but this lone physical copy of the ‘Poetical Essay’).

On one occasion Michael finds himself co-examining a Ph.D - the oral examination or ‘viva’. His colleague, it turns out is a Shelley scholar.

Cut to: Book-lined room in a university - think ‘Educating Rita’...The colleague is, let’s say, the one played by Michael Caine.

I’m, let’s say...er...an English version of Elliott Gould as campus radical teacher in that film ‘Getting Straight’ (1970)...

Caine and Gould-Rosen are chatting. Before the Ph.D.student comes in. Gould-Rosen asks Caine about the ‘Shelley thing’, as he calls it. Caine says, ‘Believe me, we’re following this closely. We’re cheering you on.’

Gould-Rosen says, ‘Are you? But why aren’t you out there complaining? Where are the petitions? Why...isn’t there a collection on behalf of the Shelley poem?’

‘I don’t know,’ says Michael Caine.

‘This could go on for years,’ says Gould-Rosen ‘It’s locked away out of sight. To all intents and purposes it’s in a bank vault. We should liberate Shelley.’

(Minor interlude here while we reflect on how the Romantics in their very different ways absorbed and recycled previous forms of poetry - Coleridge taking the old ballad form of the Ancient Mariner, Wordsworth taking the ‘Reverdie’ and the ‘Aventure’ for ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’ and Keats absorbing Shakespeare. All texts are intertextual, including this little talk with its references to films, but, we reflect, that all this is a rather un-Romantic idea, not leaving much room for the ‘imagination’. )

Anyway, back with the fate of the ‘Poetical Essay’ between 2006 and 2015 - the lost nine years.

The poem is, in this time as I say, deliberately hidden from view, concealed, occluded.

(One sadness as a digression. The poet Adrian Mitchell died in 2008. Though William Blake was Mitchell’s great hero, he was also a Shelley enthusiast and if any living poet of the late twentieth, early 21st centuries could claim to have written in the tradition of ‘The Masque of Anarchy’, it’s Adrian. At the memorials for Adrian, I ponder on how wrong it is that he lived but also died in a time when the poem had been discovered but not revealed.)

The story gathers pace. Rosen gathers at some point in his phone calls with Quaritch that Quaritch has moved on from being the seller of the ‘Poetical Essay’. Quaritch has bought it.

The ‘Poetical Essay’ has become an investment.

But is it now available to be seen and read? No.

Next: the pamphlet is displayed at an exhibition. But as it’s only the title page, it seems more like a tease than anything else.

Then comes The Big Day: the Bodleian library announces in November 2015 that it had...“acquired its 12 millionth printed book: a unique copy of a pamphlet entitled Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things...

[it goes on...]

... The acquisition is a momentous event for the public, for scholars, the University and the Bodleian Libraries. Known to have been published by Shelley in 1811 but lost until recently, [there’s that ‘lost’ word again] Shelley’s Poetical Essay is, thanks to the generosity of a benefactor, now freely available to all in digitized form.

The Bodleian Libraries are extremely grateful to Mr Brian Fenwick-Smith and Mr Antonio Bonchristiano for their generous support of this project.”

Yes, the Shelley One was released. The whole strange nine-year-long episode came to an end.

The poem is now available at archive.org

or with full commentary at

poeticalessay.bodleian.ox.ac.uk

You can find Woudhuysen’s original article at the TLS archive, as well as articles about the poem in various places by, for example, Alison Flood, John Mullan, Michael Rossington, Michael Caines or Michael Rosen.

(Editor or watch Stephen Hebron leaf through the manuscript below)

I’ll finish with a few lines from the poem, to give you the flavour of what John Mullan called Shelley’s outrage:

Here’s the opening:

‘Destruction marks thee! o’er the blood-stain’d heath

Is faintly borne the stifled wail of death;

Millions to fight compell’d, to fight or die

In mangl’d heaps on War’s red altar lie.’

Later...

‘Ye cold advisers of yet colder kings,

To whose fell breast, no passion virtue brings,

Who scheme, regardless of the poor man’s pang,

Who coolly sharpen misery’s sharpest fang,

Yourselves secure.”

‘The fainting Indian, on his native plains,

Writhes to superior power’s unnumbered pains;

The Asian, in the blushing face of day,

His wife, his child, sees sternly torn away;’

End of the poem:

“Man must assert his native rights, must say

We take from Monarchs’ hand the granted sway;

Oppressive law no more shall power retain,

Peace, love, and concord, once shall rule again,

and heal the anguish of a suffering world;

Then, shall things, which now confusedly hurled,

Seem Chaos, be resolved to order’s sway,

And error’s night be turned to virtue’s day.”

Michael Rosen (pictured with Keats-Shelley House Curator, Giuseppe Albano)