Q: Could you give us a little background to ‘Writ in Water’?

AG-C: ‘Writ in Water’ is a play written to commemorate the Bicentenary of Keats’s death on 23 February 1821. As such it balances my play ‘Rebel Angel’ broadcast on 30 October 1995 by the BBC, to celebrate the Bicentenary of his birth. The plays’ first broadcasts therefore reflect the exact length of the poet’s short life. The BBC will be repeating ‘Rebel Angel’ later in the year- maybe round October again – along with a repeat of ‘Writ in Water’.

Q: What events in John Keats’ life are covered in the story?

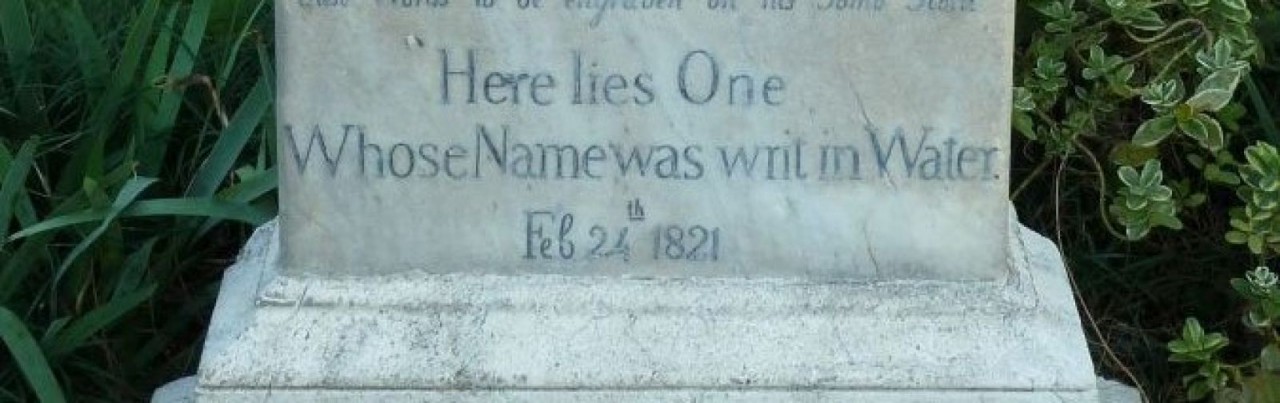

AG-C: The play itself dramatises Keats’s farewell to his fiancée Fanny in Hampstead, his embarkation and sea voyage to Naples with his friend Joseph Severn, braving a fierce storm in the Bay of Biscay, his ten days quarantine in Naples harbour, his travel to Rome, his brief period of reasonable health there and then his distressing illness, leading to his painful death in Severn’s arms. We open with Keats’ pre-dawn burial in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome and concludes with a later visit by his doctor and Severn to place flowers on his grave, where they ponder his request that his tombstone should merely say ‘Here lies one whose name was writ in water’.

Q: How did you go about researching Keats’ final months?

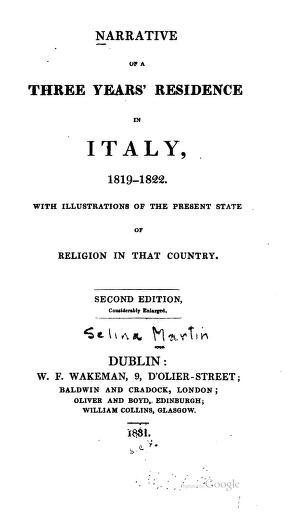

AG-C: I have read all the standard biographies of Keats and Severn, and the latter’s letters that he wrote during Keats’s last agonising weeks. I also found Selina Martin’s book ‘Narrative of a Three Years’ Residence in Italy, 1819-22’ fascinating, as she was nursing a dying niece in Rome as Keats was dying, and her family were visited by Dr Clark, Keats’s physician and Rev Woolf, who was to perform Keats’s burial service and both of whom are characters in my play. The play is largely historically very accurate, but I have altered a few details, such as The Princess Paulina (Napoleon’s sister) being attracted to Keats in Rome, rather than his riding companion, a fellow consumptive army officer [Isaac Elton]. Where possible I have used Keats’s own words, as in his final death scene.

Also my research into Keats generally and for the plays have taken me to most of the places that occur: the garden and Keats House in Hampstead, Tower Wharf, Naples, and in Rome, the Lateran Gate, the route through Rome to the Piazza di Spagna, the Spanish steps and Keats’s House, the Pincio gardens, the room in which he died and the Cemetery. Cherry [Cookson, director of ‘Writ in Water’] had hoped to do some site-specific recording in some of these places, but the pandemic intervened – and matters of budget!

Q: There are obvious challenges of turning this story into a radio drama. How did you go about doing this?

AG-C: The play is not just a biographical travelogue, but tries to capture the intensity of Keats’s relationships and his moments of intense happiness, creativity and the physical and mental agony of his last days as he was dying of consumption, yearning for a death that would not come, imploring Severn to give him his bottle of laudanum so he could end his own life. Billy Howle, as Keats, and Callum Woodhouse, as Severn, are deeply moving in these final scenes, and Saffron Coomber is wonderful as Fanny Brawne in her happier scenes with the young flirtatious poet.

Q: Could you tell us a little more about the recording itself, and the excellent young cast. How did the production compare to ‘Rebel Angel?

AG-C: Despite their present TV successes – Billy leading in ‘The Serpent’, and Callum as Leslie Durrell and also a young Tristan Farnon in ‘All Creatures Great and Small’ – this was their first radio work, and made during the restrictions and distancing of lockdown.

‘Rebel Angel’, directed by Richard Wortley (once married to Cherry Cookson) and starring Julian Rind-Tutt as Keats, was recorded in the full luxury of the top radio studio of Broadcasting House, with studio managers producing live sound effects and the actors performing almost as on stage. I remember a large wheelbarrow full of earth being emptied onto the studio floor, so the grave robbers could dig real earth with real spades. And the actor playing Edmund Kean, performing Othello, appeared in full period costume and a chair leg was sawn in two as an amputation was performed, producing a most grisly effect.

Q: What impact did the Covid pandemic have on the actual performance and recording?

AG-C: ‘Writ in Water’ was created under the most difficult of circumstances in a small studio in north London, with solely the actors, the director and one engineer. Even I could only be briefly at the recording. We were all masked, except the actors when actually performing and despite the wonderful illusion you get in the play, they were socially distanced at their microphones. I think people don’t realise how usually radio plays are much more acted out than one thinks. One would have expected in the death scene for there to be a bed in the studio, on which Billy would have been lying, cradled by Callum. Not so in this case, as they stood apart separated by a screen. All the music and complex sound effects were added later. Scenes like the near shipwreck are all the more remarkable for this.

Q: These final months are the most forbidding part of Keats’ story – filled with physical suffering and emotional anguish, and devoid of happiness and creativity. Is that what you found? And how do you present this John Keats?

AG-C: I’m afraid that there is very little that is uplifting or joyful about Keats’s journey or time in Rome. He was heartbroken by his separation from Fanny, he had no hope of an afterlife and he was in great mental and physical pain. Worst of all he felt that he had made no impact as a poet and that his name had been written in water. We now know how untrue this was and, indeed, back in England some excellent reviews were greeting his final book of poems published in 1820. It is just possible that he became aware of this and I take the liberty of making this assumption – to a certain extent.

AG-C: I have also tried to celebrate his happiness with Fanny, his care for Severn and his creative triumphs in ‘Bright Star’ and the ‘Ode to a Nightingale’. There is more boisterousness and jollity in ‘Rebel Angel’, which explores Keats’s decision to abandon medicine for poetry as a very young man. A stage version of this play was performed a few years ago in The Old Operating Theatre at Guy’s Hospital.

Q: 200 years after Keats’ birth and, now, his death, how would you describe his status in the artistic pantheon? Will we be celebrating him 200 years from now?

AG-C: Over the 200 years Keats’s reputation has continued to soar, while that of some of his contemporaries have risen and fallen. His early death, doomed love, appealing personality, handsome looks and approachable and luxuriant poetry have caught the imaginations of generations and he has a particular appeal to young readers. Both his life and poetry possess a complex pattern of contrasts and opposites that create a wonderful artistic totality. He is often spoken of in comparison to Shakespeare - and indeed he yearned to write great plays. His reputation will continue to rise.

Q: Thank you Angus. A final question. Do you have a favourite Keats poem or poems?

AG-C: You ask about favourite poems. I love the early ‘I Stood Tiptoe’, with its sensitive and detailed fresh observation of nature, also ‘The Eve of St Agnes’ and all the great Odes, particularly Autumn and Nightingale. I struggle with Endymion and I find the Victorian favourite Isabella, or The Pot of Basil too gothic and over- written for my taste. And of course, his Letters are remarkable. I have made use of them in these two plays and in the play ‘Life is But a Day’ due to be performed as part of the Gala Celebrations of the Keats-Shelley Memorial Association on 23rd October this year in the Palazzo D’Oria in Rome.

James Kidd

Angus Graham-Campbell’s ‘Writ in Water’ is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 at 2.15pm, 23rd February 2021, to mark the 200th anniversary of John Keats’ death.

Listen to ‘Writ in Water’ at Radio 4’s website, where it will be available to stream immediately afterwards.

Learn more about John Keats’ Final Journey from London to Rome on our interactive, multi-media Google Earth map.

Read about 2021’s Keats-Shelley Prize.

Read about 2021’s Young Romantics Prize.

Click the link for all the latest news about our KS200 Bicentenary Programme.