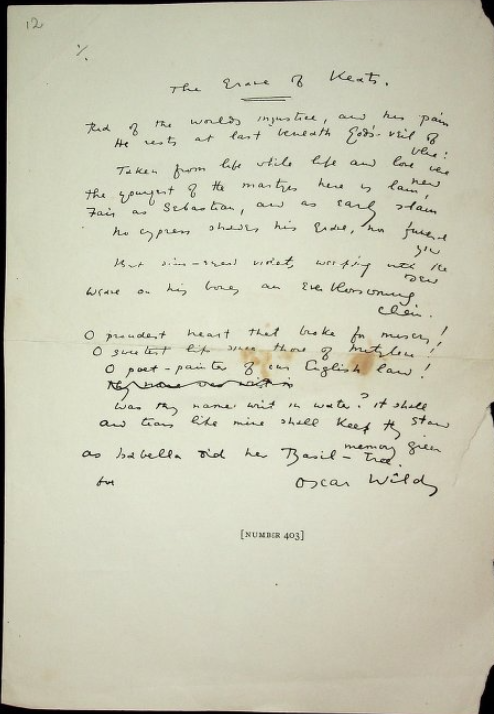

The Grave of Keats

Rid of the world’s injustice, and his pain,

He rests at last beneath God’s veil of blue:

Taken from life when life and love were new

The youngest of the martyrs here is lain,

Fair as Sebastian, and as early slain.

No cypress shades his grave, no funeral yew,

But gentle violets weeping with the dew

Weave on his bones an ever-blossoming chain.

O proudest heart that broke for misery!

O sweetest lips since those of Mitylene!

O poet-painter of our English Land!

Thy name was writ in water—it shall stand:

And tears like mine will keep thy memory green,

As Isabella did her Basil-tree.

ROME.

When Oscar Wilde wrote this sonnet in 1877, the title was the less prosaic and more Roman ‘Heu Miserande Puer’: ‘Alas! Unfortunate Boy’. It was also a quite different poem:

Rid of the world’s injustice and its pain,

He rests at last beneath God’s veil of blue;

Taken from life while life and love were new,

The youngest of the martyrs here is lain,

Fair as Sebastian and as foully slain.

No cypress shades his grave, nor funeral yew.

But red-lipped daisies, violets drenched with dew.

And sleepy poppies, catch the evening rain.

O proudest heart that broke for misery!

O saddest poet that the world hath seen!

O sweetest singer of the English land!

Thy name was writ in water on the sand.

But our tears shall keep thy memory green,

And make it flourish like a Basil-tree.

The sestet is substantially different, leaving no overwrought stone unturned, nowhere more so than in Wilde’s quotation of Keats’ epitaph whose hymn to futility is turned up to eleven. Not only is the union of ‘writ in water’ to ‘sand’ superflous, it forms a strange and unfortunate image of Keats playing on a beach.

The sonnet was re-titled and re-written by the time Wilde included it in a letter of thanks to Mrs Emma Speed, the daughter of Keats’ brother George, who had attended a lecture he had given in Kentucky (12th February 1882). Wilde had quoted Keats’ sonnet ‘On Blue’ with approval. Speed returned the favour by sending Wilde an original manuscript, which prompted Wilde’s poetic thank you.

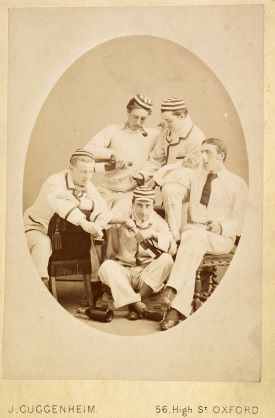

Wilde visited Keats’ grave in late April 1877 (probably sometime between the 23rd and 25th) when he was still studying at Magdalen College, Oxford. He was accompanied by two university acquaintances, David Hunter Blair and William ‘Bouncer’ Ward. They made a somewhat unlikely trio: the sociable Ward would become a lawyer; Hunter Blair would become a Benedictine monk and later Abbot of Fort Augustus.

Wilde recorded the visit in an article for the article for the Irish Monthly that July. A tone of mild bathos is established from the start, when he describes passing the famous pyramid, which he once supposed to be the sepulchre of Remus: ‘but we have now, perhaps unfortunately, more accurate information about it, and know that it is the tomb of one Caius Cestius, a Roman gentleman of small note, who died about 30, b.c.’ The friction between myth and reality, Romantic vision and anti-climactic sight-seeing, absence and presence will haunt Keats’ grave.

Cestius wasn’t the ‘dead man’ Wilde was after. But, he concedes in a rolling sentence that gathers a fair amount of lyrical speed, his ‘pyramid will be ever dear to the eyes of all English-speaking people, because at evening its shadow falls on the tomb of one who walks with Spenser, and Shakespeare, and Byron, and Shelley, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, in the great procession of the sweet singers of England.’

Just in case the reader isn’t crystal clear who exactly Wilde is seeking, he adds: ‘And the name of the young English poet is John Keats.’

Wilde calls Richard Monckton Milnes and Percy Shelley as witnesses to (in Milnes’ phrase) ‘one of the most beautiful spots on which the eye and heart of man can rest’. Wilde by contrast found little overt beauty in the spot; or seems helplessly distracted by unsightly examples of man-made hideouosness. He positively recoils from Warrington Wood’s marble medallion portrait of Keats, sculpted shortly before: ‘The face is ugly, and rather hatchet-shaped, with thick, sensual lips, and is utterly unlike the poet himself, who was very beautiful to look upon.’ At this point, Wilde calls another witness, a lady who saw Keats in person at one of Hazlitt’s lectures. According to her, the poet ‘“lives in my mind as one of singular beauty and brightness; it had the expression as if he had been looking on some glorious sight.”’

Wilde isn’t much more enthusiastic about by Sir Vincent Eyre’s acrostic to Keats, which is dismissed as ‘some mediocre lines of poetry.’ He modifies this distaste, of the poem at least, in a letter to Milnes written not long after, judging the poem ‘fairly good’ (circa 17 May 1877). The medallion profile though is beyond salvation. It is, Wilde complains, ‘extremely ugly[…]I am sure a photograph of it could be easily got, and you would see how horrid it is.’ He then begs Houghton to use his influence to replace this ‘ugly libel of Keats’ with ‘a really beautiful

memorial’ – a fervent hope that is repeated in the published article.

Wilde in truth sounds pretty underwhelmed by the visuals in general, bemoaning that ‘this time-worn stone and these wild flowers [which] are but poor memorials of one so great as Keats’ – all the more so in a city like Rome ‘which pays such honour to her dead’.

Does this explain the visit’s most famous, and even infamous moment when Wilde supposedly prostrated himself on the grave itself? Perhaps Oscar simply wanted to brighten the place up a bit, give it a touch of some much-needed glamour?

There is a more serious context for Wilde’s flamboyant submission. The source of the incident is Hunter Blair, who mentions it in an article for The Dublin Review in 1938. Back in 1877, Davies was a fairly recent convert to Roman Catholicism and hoped that Wilde might follow his lead. Wilde’s attractions to the faith had already caused arguments in the holiday, this time with the Reverend John Pentland Mahaffy, his very Protestant former professor in ancient history at Trinity College, Dublin. The pair had toured Europe two years earlier, bypassing Rome in favour of Florence, Padua and Venice among others. In 1877, they returned to Italy, with a small detour in Greece.

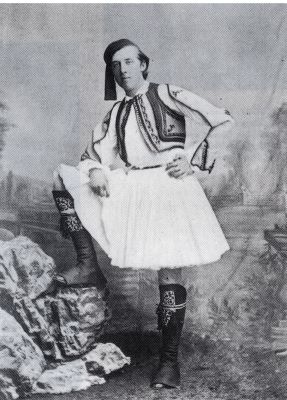

When Wilde expressed a desire to include Rome on their itinerary, Mahaffy was outraged. ‘No, Oscar, we cannot let you become a Catholic but we will make you a good pagan instead.’ Wilde insisted, and left Mahaffy to join Hunter Davies and Ward, even though it meant missing the start of the next university term and risking rustication – something that duly came to pass.

On the same day that Wilde visited Keats’ grave, Hunter Blair dealt the biggest card imaginable in the poker game for Wilde’s immortal soul: he arranged an audience with Pope Pius IX. The experience must have been a profound one, for Wilde was left speechless during the carriage ride back to the Hotel d’Inghilterra, only a stone’s throw from 26 Piazza di Spagna where Keats had died. Wilde locked himself in his room and promptly composed two poems in honour of the afternoon.

But it was poetry that would eventually triumph. Later that evening, the three friends set out from the Hotel. Their destination was the Papal Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls, which took them past the Cimitero Acattolico, which stands less than two miles to the north on Via Ostiense.

To Hunter Blair’s dismay, Wilde ‘could not be dissuaded from alighting at the Protestant cemetery and prostrating himself on the turf to venerate the grave of John Keats.’ No doubt the ‘Acattolico’ nature of the place was enough to give Blair pause, but what must have really signalled his defeat was Wilde’s very public, possibly defiant and near-blasphemous act of submission before a poet rather than a Pope.

It is hard not to be moved by the sheer verve – and nerve – of Wilde’s exuberant, sexy passion. It is there in his admittedly florid, erotic (and eerily autobiographical) conception of Keats as ‘a Priest of Beauty slain before his time’. The article markedly doesn’t mention either Hunter Blair or William Ward, religion or the Pope. It is as if there is just Wilde and Keats, or even Oscar and John. His transformation of a saint’s ecstatic vision into a communion between artists expands to include Guido Reni’s Saint Sebastian, which ‘came before my eyes as I saw him at Genoa, a lovely brown boy, with crisp, clustering hair and red lips, bound by his evil enemies to a tree, and, though pierced by arrows, raising his eyes with divine, impassioned gaze towards the Eternal Beauty of the opening heavens.’

Wilde’s adoration is whirl of sexual attraction for and empathy with Keats, explicitly as the victim of brute, retrograde critics. Part of the allure, as Wilde’s sonnet makes clear, are those parts of the poetry that had so unnerved and disgusted those ‘Malicious’ reviewers: the sensual, lyrical, effeminate, transgressive and languishingly erotic:

But gentle violets weeping with the dew

Weave on his bones an ever-blossoming chain.

The implication, that poetry can effect resurrections as surely as religion, seems to signal that a decision had been made. Oscar Wilde was neither Protestant nor Catholic; he was an Artist.

This would be confirmed in 1885 in a letter to the Reverend J Page Hopps that suggests he has rethought his objections to the unassuming memorial. ‘Keats’s grave is a hillock of green grass with a plain headstone,’ Wilde wrote in praise of its simplicity, before concluding in a word that suddenly speaks volumes. ‘And is to me the holiest place in Rome’.

James Kidd

Read more about 2021’s Keats-Shelley Prize here.

For 2021’s Young Romantics Prize, click here.