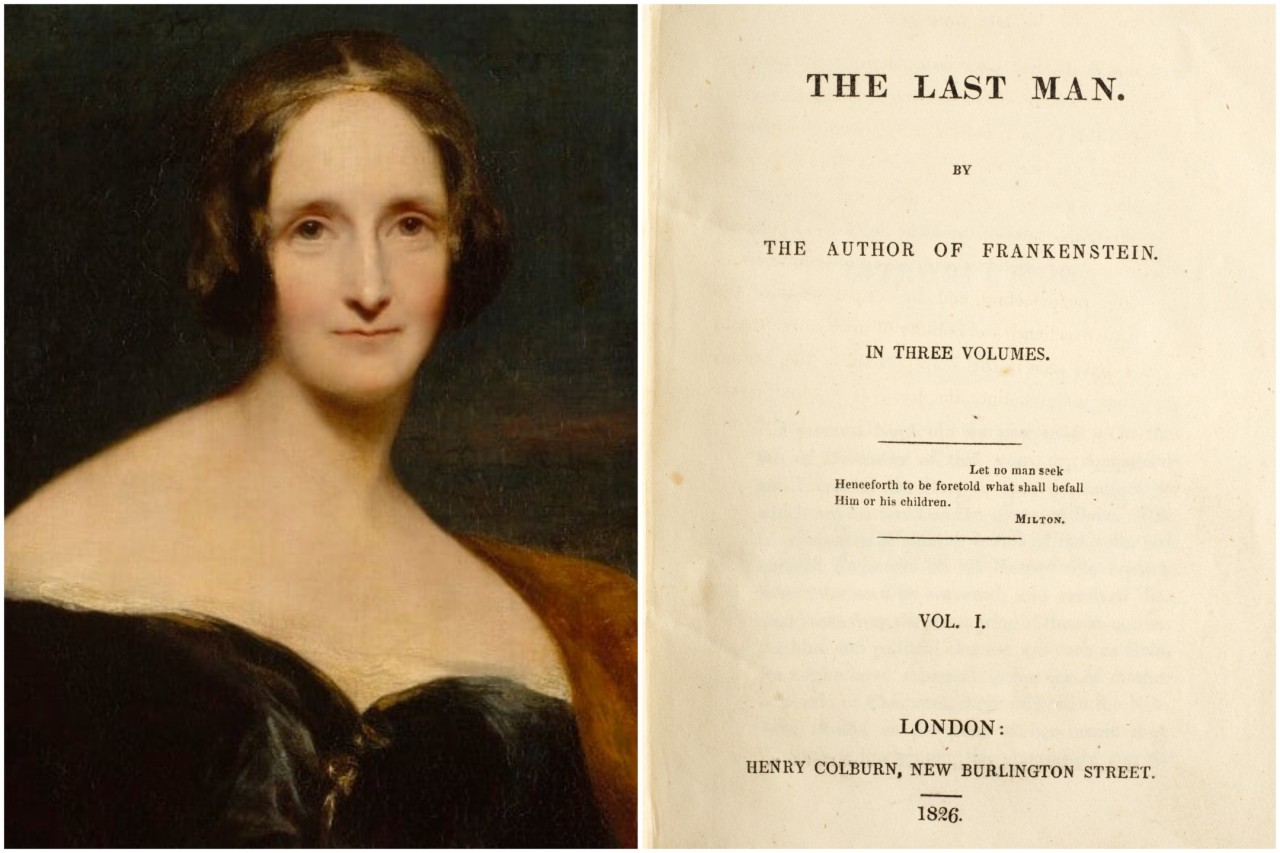

Published in 1826, after the deaths of both Mary Shelley’s husband Percy and her friend Lord Byron, The Last Man has long been regarded as a roman à clef, disguising the members of Mary’s treasured circle of friends as fictional characters. As she wrote in her Journal on May 14th 1824, she considered herself to be the Last Man: “feeling myself as the last relic of a beloved race, my companions, extinct before me -”

The Plot

During a visit to the cave of an ancient prophetess, the Sibyl, near Naples in December 1818, the narrator and a companion find some leaves bearing inscriptions. These are deciphered to reveal a story narrated by ‘the Last Man’, Lionel Verney.

The first volume of Shelley’s three-decker book introduces the main characters and explains how their stories intertwine at the time of the abdication of the King of England in 2073. The philanthropist prince Adrian (based on Percy Shelley) befriends Lionel Verney (Mary Shelley), introducing him to the pleasures of literature and philosophy. Their mutual friend, the sensual and strong-willed Lord Raymond (Lord Byron), becomes Lord Protector and decides to fight in Greece against the Turks, so that England can extend its influence in Asia.

At the beginning of the second volume, after the conquest of a ghastly and desolate Constantinople – where Lord Raymond dies in an explosion – a terrible plague begins to spread towards the West and finally reaches England. In the third volume, what is left of the decimated English population flees towards southern Europe, with the vain hope of surviving in a milder climate. At the end of the novel, in 2100, Lionel Verney remains the last man on earth: after a prolonged residence in Rome, he abandons his diary and decides to sail across the Mediterranean, looking for other survivors.

The Failure of Philosophical, Political and Religious Ideals

In her description of a devastating plague, Mary Shelley seems to undermine the philosophy of her father, William Godwin. He believed in the perfectibility of mankind, and that the unlimited power of the human mind – once freed from institutional restrictions – could lead to the elimination of diseases and death. The vision of an earthly paradise put forward by Adrian after the defeat of the Turks, where “poverty w[ould] quit [men], and with that, sickness,” is shared only by the ridiculous astronomer Merrival, who expects it take shape in a hundred thousand years – when, as the reader knows, mankind will probably be extinct.

The plague also offers a solution to the fierce debate in 1820s England over the French Revolution and the question of hereditary rank and the equality of rights. As one characters remark, “Death and disease level all men.”

In the declining world of The Last Man, not even religion can bring relief to mankind. No prayers are offered to a distant God, and the only preacher featured in the story – the head of the fanatical sect of the “Elect” – is actually an impostor who gained power by pretending that his followers would become immune to the disease.

The Failure of the Romantic Idea of Art

At the beginning of the novel, Adrian contemplates the English countryside, sharing with Lionel Verney his appreciation of the landscape. Later, however, the Romantic ideal of human regeneration through the deep communion with nature is openly undermined. The plague affects only humans, while plants and animals continue to thrive.

Art is frequently portrayed as cruelly illusionary. The melody of Haydn’s oratorio The Creation (inspired by the Book of Genesis) is heard by the survivors when they are in Geneva, and immediately interpreted as a good omen. Lionel and Adrian trace it, however, to a young woman dying of the plague, who is trying to soothe the sufferings of her blind father with music. Later the Last Man, surrounded by lifelike statues in Rome, deludes himself that one day they may turn into human beings. Mary Shelley even goes so far as to question the significance of writing: after all, Lionel Verney’s story is addressed to a posterity that will probably never exist.

The Failure of Ethnocentrism

At the very beginning of the novel, England is described by Lionel as a “vast and well-manned ship, which mastered the winds and rode proudly over the waves.” The frequent use of a colonial imagery, the unmistakable display of imperialistic ambitions and the arrogance of some characters have led the critic Alan Richardson to assert that The Last Man “belongs squarely in the tradition of British colonialist discourse.” Unlike the better-intentioned Byron, his fictional alter ego Lord Raymond wants to unite with the Greeks to “take Constantinople and subdue all Asia.” Another character, the “democrat” Ryland, makes the absurd claim that

[the plague] is of old a native of the East, sister of the tornado, the earthquake, and the simoom. […] It drinks the dark blood of the inhabitant of the south, but it never feasts on the pale-faced Celt. If perchance some stricken Asiatic come among us, plague dies with him, uncommunicated an innoxious.

Paradoxically, the plague arrives in England from a former colony, America. As the critic Kari Lokke has pointed out, the epidemic is “a product of imperial and colonial contact” between East and West, prompted by English greed for power and leadership. The opening portrayal of England as a ship has its ironic counterpart in the closing scene, which features the Last Man about to sail off in his little boat. This time the traveller is not heading towards glory and adventure, but towards the unknown – probably death.

A Warning

After such a long list of failures and catastrophes, one wonders what positive message the novel might offer. It shouldn’t be forgotten that the actual story takes place in 1818, and that the narrative of The Last Man is only a prophecy of the Sybil – or rather, what the decipherer understood by putting together the “scattered, unconnected” and “unintelligible” fragments of leaves. The ominous epigraph from Paradise Lost, “Let no man seek/ Henceforth to be foretold what shall befall/ Him or his children” – words that Adam utters after the Archangel Michael shows him a vision of the Flood – is balanced by the knowledge that, in this case, no archangel is involved and the future could turn out to be very different. Moreover, Mary Shelley seems to suggest that – as Macbeth knew all too well – being deeply swayed by prophecies may even trigger one’s ruin.

To conclude, by highlighting past and present mistakes, Mary Shelley offers The Last Man as a warning to her readers, giving them the possibility to write a different ending for their collective history and personal stories.

Elisabetta Marino

This is a shortened version of Elisabetta Marino’s “Re-reading the Romantics in the XXI Century: The Last Man by Mary Shelley (1826)”, in Englishes, n. 40, Anno XIV, Pagine, Roma, 2010, pp. 123-133.