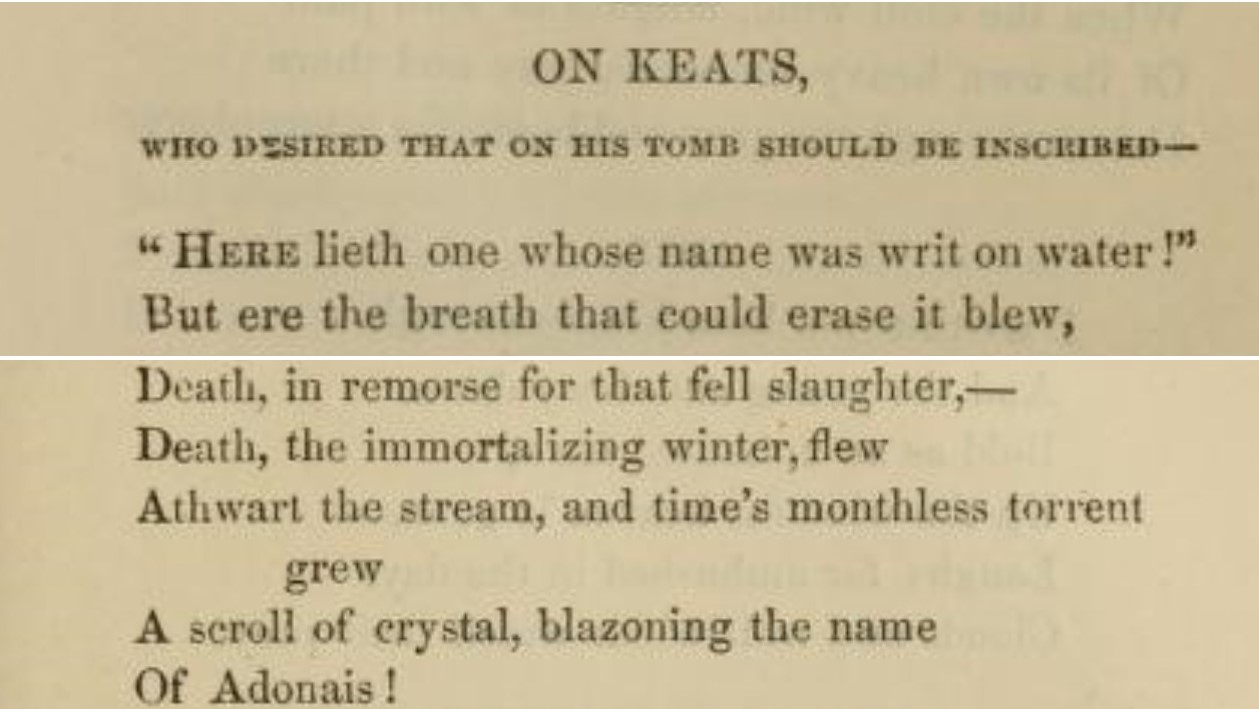

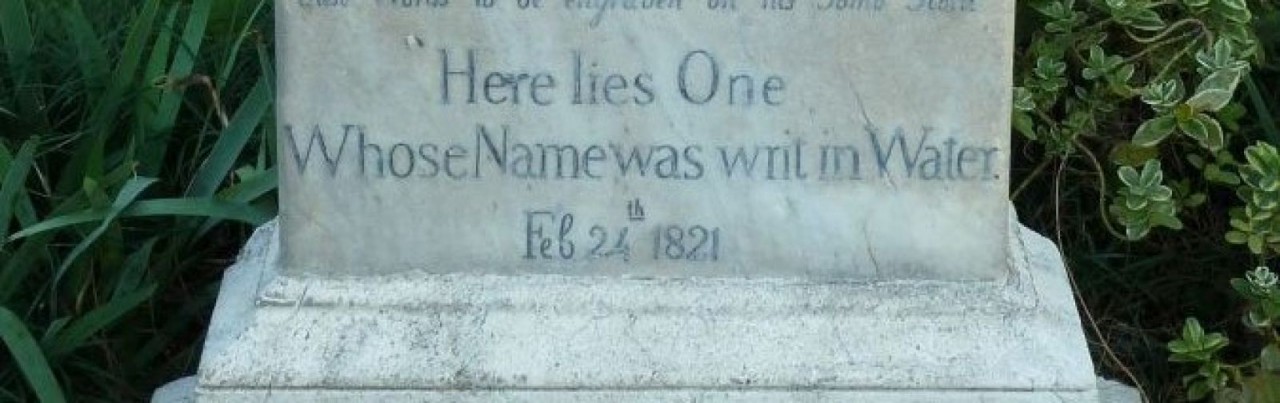

“Here lieth One whose name was writ on water.”

But, ere the breath that could erase it blew,

Death, in remorse for that fell slaughter,—

Death, the immortalizing winter, flew

Athwart the stream,—and time’s printless torrent grew

A scroll of crystal, blazoning the name

Of Adonais!

PB Shelley

A fragment of a sonnet possibly, or possibly a stanza from Adonais. First published by Mary Shelley in 1839’s Collected Poems, from Shelley’s notebooks. There are two further drafts with minor changes and the occasional addition. In one version, the ending goes like this:

‘A scroll of chrystal, blazoning thy name

On our cold hearts on our ?hard

A Adonais and

On on’

In a second draft ‘Death’ in line three is ‘half-repetentant’ of so fair a slaughter. The second ‘Death’ flies ‘Athwart the flood’. There is also a little coda that echoes Adonais itself:

‘Of Adonais for whom inquired & knew

Her son an?

?The boy?’

Unless of course Shelley was simply writing down the name of a local pub.

Still, the snippet is intriguing, in part because it is probably the first (but far from the last) appearance of Keats’ epitaph in verse. It also illustrates the way in which ‘writ in water’ was itself ‘writ on water’, especially to begin with: that is to say, written incorrectly. As early as 1822, it provides a deliberately modulated refrain to the obscure ‘Stanzas To the Memory of Mr Keats, who died on this day twelvemonth’ (written on 23rd February 1822), which was published in the also obscure The Imperial Magazine: Vol 4 (1822). To give an example, the first stanza ends: “O let my name be writ in water”. What is even more striking is that the author, known only as ‘H.D.’, glosses the epitaph, and claims that it was ‘well known’ even then.

A year later, ‘writ in water’ is quoted and glossed again, also with approval, by another pseudonymous poet Gerard Montgomerie, aka John Moutrie. But while Moutrie quotes ‘writ in water’ correctly in his Byronic homage La Belle Tryamour, he misquotes it (’written in water’) in the explanatory footnote.

Both poems, composed by what seems like a new generation of poets, were in circulation before the epitaph was made public by Keats’ own friends and acquaintances. Even these it seems can’t get the line quite right. Leigh Hunt in 1824’s Lord Byron and Some of His Contemporaries adds a comma after ‘Here lies One,’.William Hone puts a little more flesh on the bones: Here lies the body of one whose name was writ in water’, in 1826’s Table-Talk.

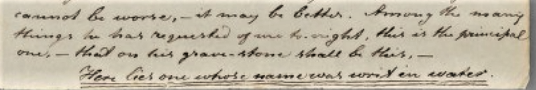

All of which raises some further questions. Is it possible Joseph Severn misheard the epitaph on 14th February 1821? If he got it right, did he write it down in capitals, as suggested by its appearance in Richard Monckton Milnes’ Life, Letters and Remains and also Hyder Rollins Keats Circle: Volume 2? While Charles Brown doesn’t capitalise the epitaph, when transcribing Severn’s Valentine’s Day letter in his 1836 Life of John Keats, he does underline it for all its worth. This is probably for emphasis, but it could suggest another hypothetical thought: is it even possible that Keats may have written it out himself?

James Kidd

Read about 2021’s Keats-Shelley Prize.

Read about 2021’s Young Romantics Prize.