2019's State of Nature Report, published today by the National Biodiversity Network, makes sobering reading. Summarised by Damian Carrington in the Guardian, it states that ‘Populations of the UK’s most important wildlife have plummeted by an average of 60% since 1970.’

Even more terrifying are findings that suggest ‘A quarter of UK mammals and nearly half of the birds assessed are at risk of extinction[…]When plants, insects and fungi are added, one in seven of the 8,400 UK species assessed are at risk of being completely lost, with 133 already gone since 1500.’

The UK is “among the most nature-depleted countries in the world”.

2019 State of Nature Report

Both the songbirds that inspired 2020’s Keats-Shelley Prize – the nightingale and the skylark – are on red lists of UK birds under the gravest risk of extinction. Included among the threats to their long-term survival are the rapid and largely man-made erosion of their natural habitats.

As John Keats might reminds us, the destruction of wild spaces, in urban areas above all, is nothing new. Accounts of his composition of Ode to a Nightingale in 1819 suggest that unchecked development was threatening the songbird's existence in England two centuries ago.

In his biography of Keats, Nicholas Roe recalls that when the poet moved to Hampstead in early 1819, Wentworth Place was ‘a large garden planted with fruit trees, a vegetable plot with a toolshed, and fields to the back and towards the Heath.’

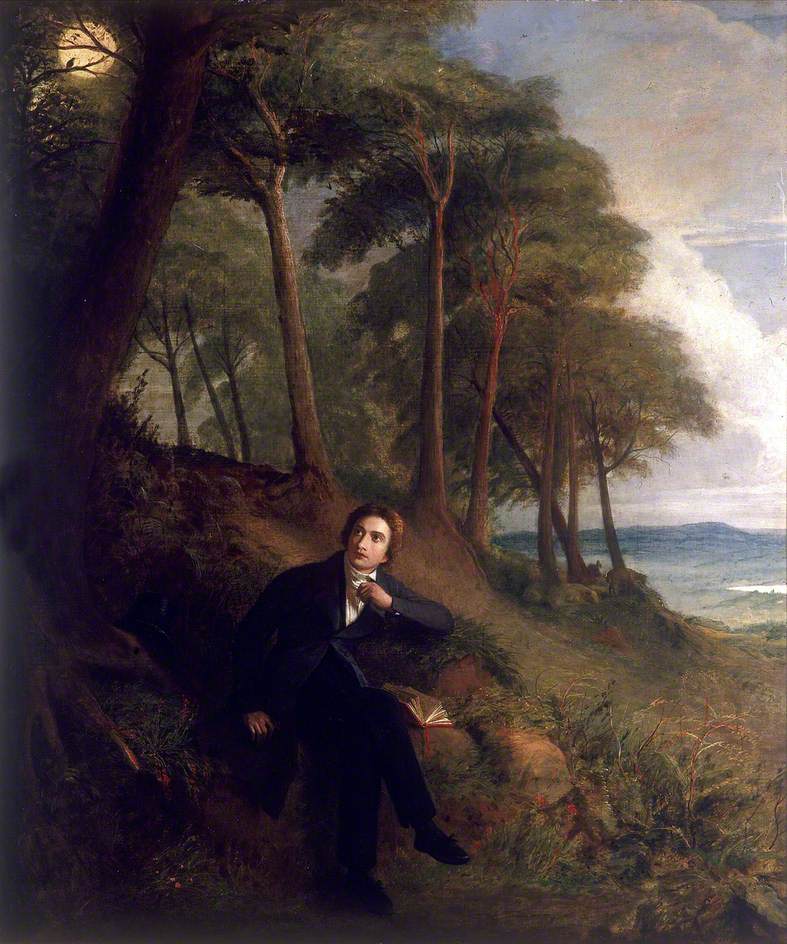

But as Roe continues, this open country ‘would not remain so for long, as speculative building was rapidly changing the landscape.’ The 'idyllic pastoral idyll' portrayed by Joseph Severn in his famous portrait ‘Keats Listening to the Nightingale’ was a fantasy: Keats ‘was in the middle of a suburban building site.’

This ‘dismaying evidence of ‘progress’' as Roe calls it drove Keats’ imagination in new ways. Retreating from the ‘march of endeavour’ outlined in his embryonic epic Hyperion, Keats found solace in memories of ‘romantic medievalism’, ‘verduous glooms and winding mossy ways,’ and a new melancholy, introspective mood that would find its purest expression in the odes he would write that spring and summer.

‘Directly opposite the garden plot where apparently Keats wrote his poem, two houses were being erected – one of many speculative enterprises in Hampstead in 1819, soon to be abandoned half-built, dingy and as if ‘dying of old age'

Nicholas Roe, John Keats

In this context, Roe argues that Keats’ ‘sense of the perilousness of the moment in ‘Ode to a Nightingale’’ is not merely related to his own protracted ill health, but the ‘inexorable advance of ‘hungry generations’[…]threatening as London’s edges pushed outwards into surrounding villages and fields[...]If in the nightingale’s ‘high requiem’ he heard a mass for himself, its ‘plaintive anthem’ was also an elegy for a landscape and way of life as ephemeral as the music he hears fading’.

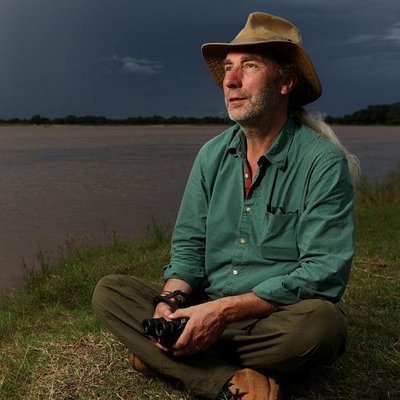

Simon Barnes, 2020’s Keats-Shelley Prize Chair, also hears the threats to nature and nightingale whispered in Keats’ famous ode.

In The Meaning of Birds, he writes: ‘The Romantic Movement was another response to loss and it was, I suppose, another kind of birdwatching.’ Keats’ poetry, like that of Wordsworth before him and Shelley alongside, ‘is filled with the conviction that really important truths can be found in the wild world, that human enrichment lay beyond the cities.’

'It was the beginning of the realisation that the breakneck pace of development was not an unambiguously good thing, and that without the wild world we are less than ourselves.'

Simon Barnes, The Meaning of Birds

For Barnes like Roe, the pleasure that Keats found in the nightingale, and Shelley in the elusive skylark, reveals a social truth as well as a literary one: that this pleasure has in the early 19th century already become inextricably linked with the songbirds’ increasing vulnerability, thanks largely to humankind’s unquenchable desire for ‘progress.’

Given 2019's even more parlous state of affairs, as detailed in the State of Nature Report, how much longer before poems, paintings and recordings are the only places left to enjoy the UK’s nightingales and skylarks?

James Kidd