2020 Keats-Shelley Prize Theme: Songbird

To mark bicentenaries of Shelley's To a Skylark and Keats' Ode to a Nightingale, and raise awareness of rising threat of extinction

‘Hail to thee, blithe spirits’…

We are pleased to announce the launch of the Keats-Shelley Prizes for 2020.

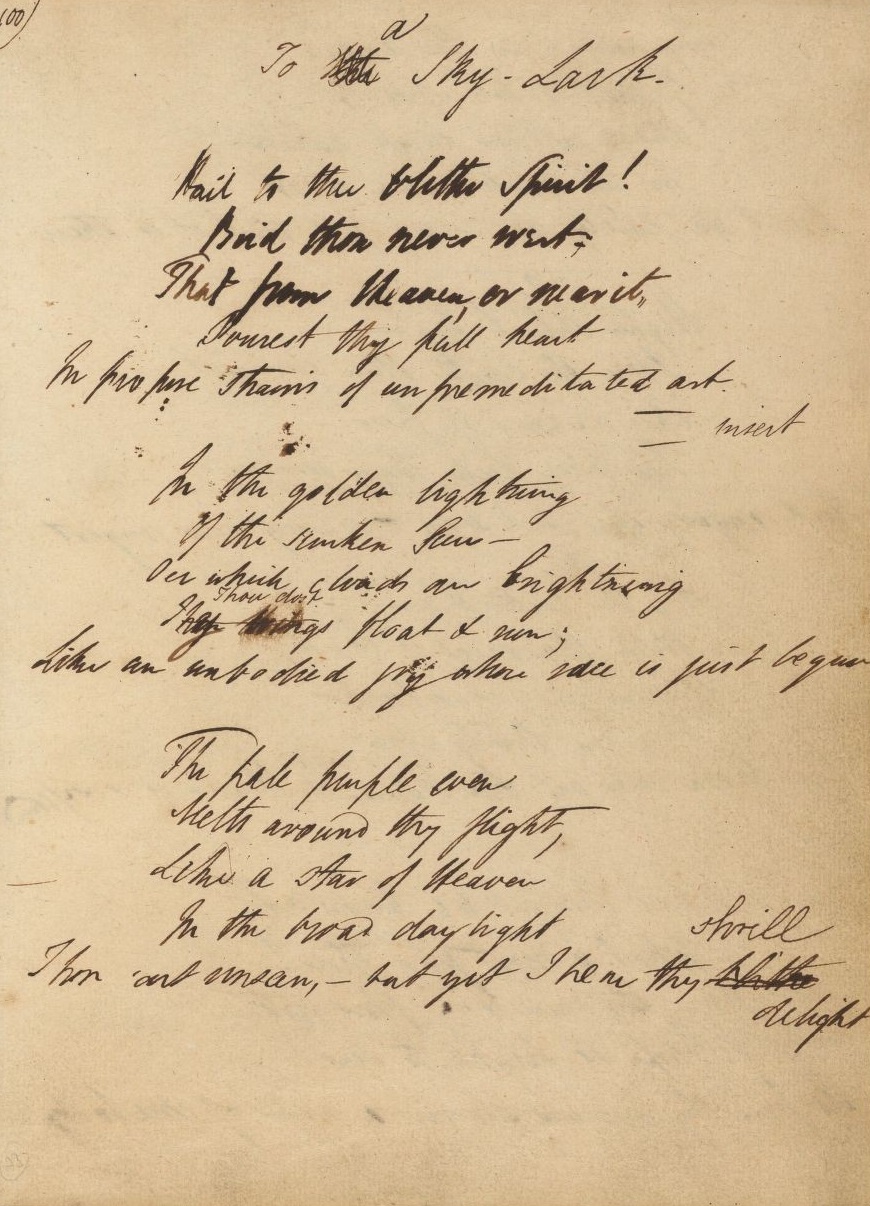

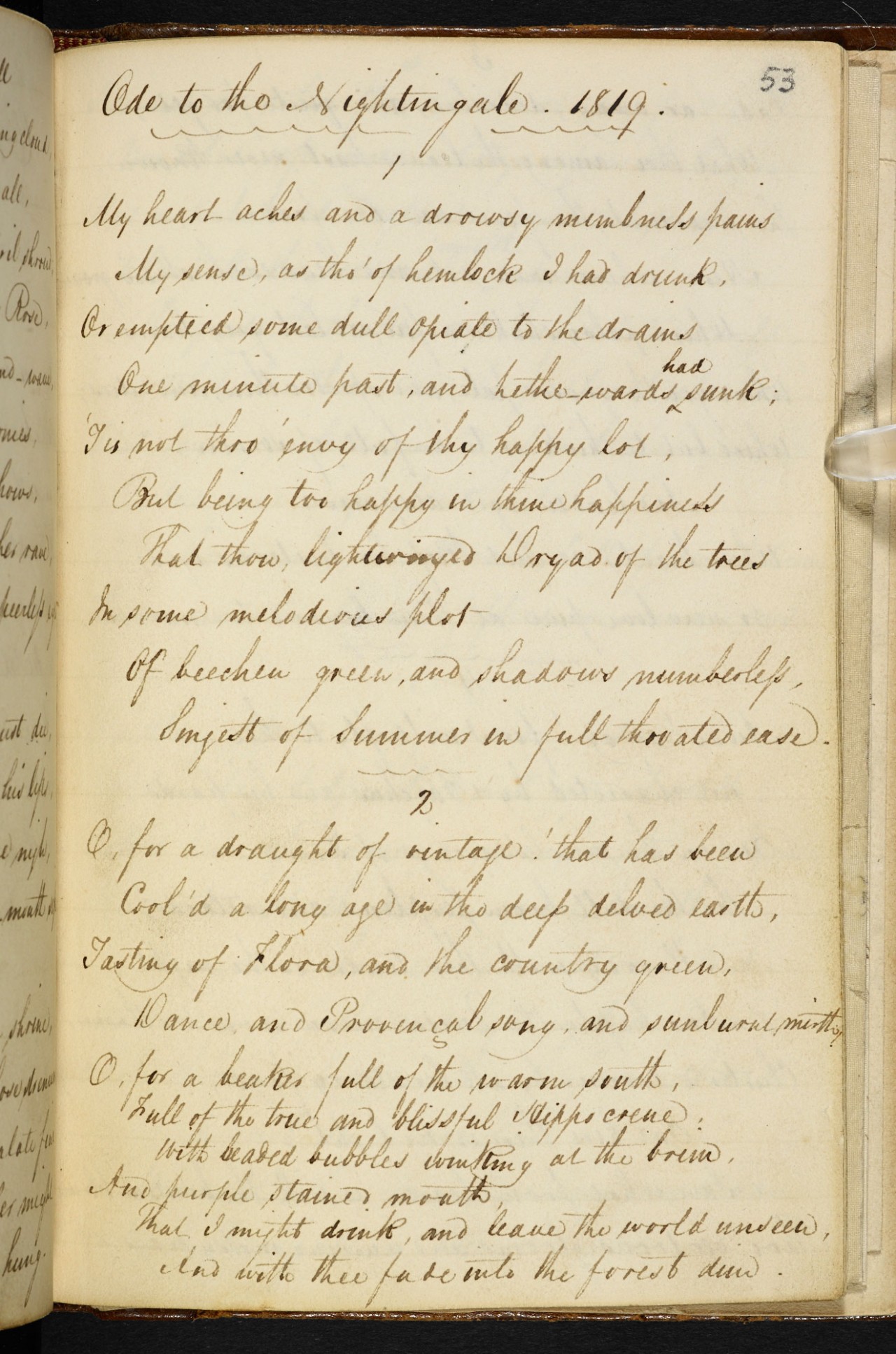

This year’s poetry theme is ‘Songbird’, which celebrates two landmark bicentenaries – the composition in June 1820 of ‘To a Skylark’ by Percy Bysshe Shelley and the first appearance in book form of John Keats’ ‘Ode to a Nightingale’.

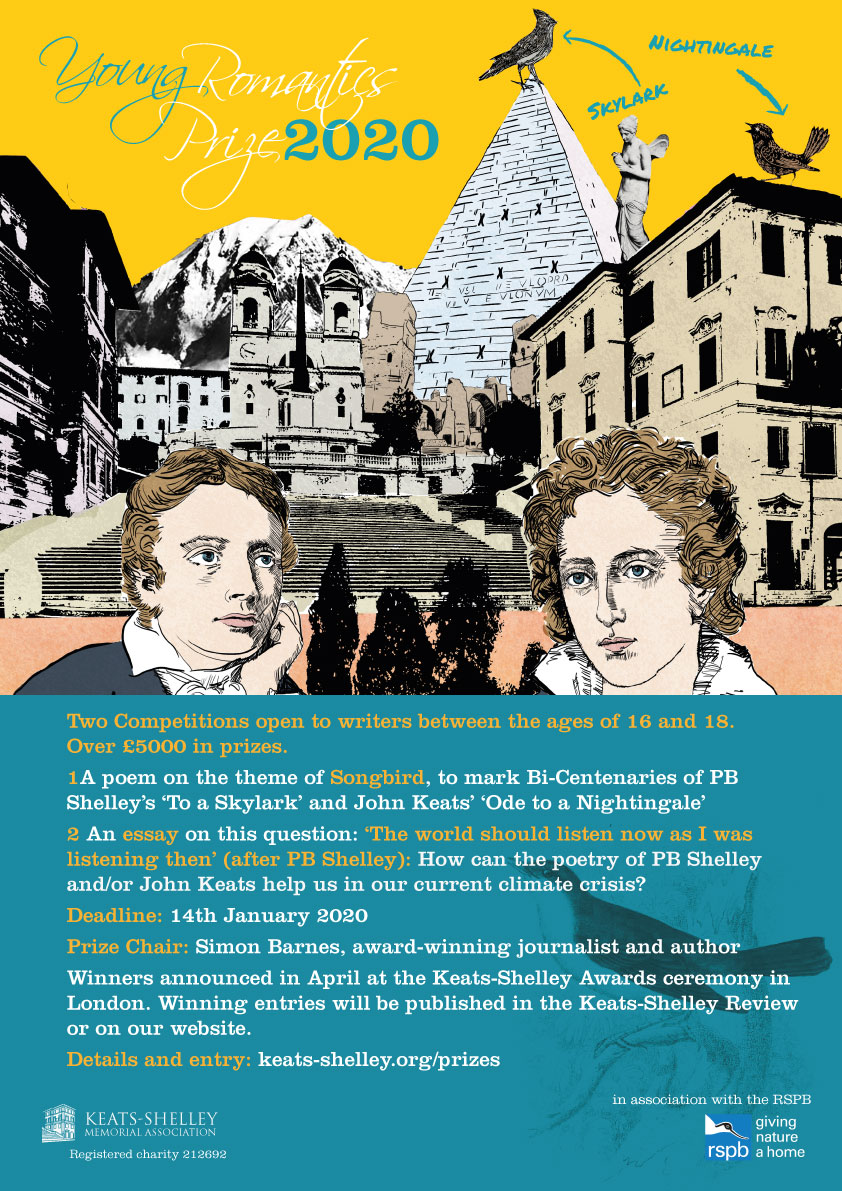

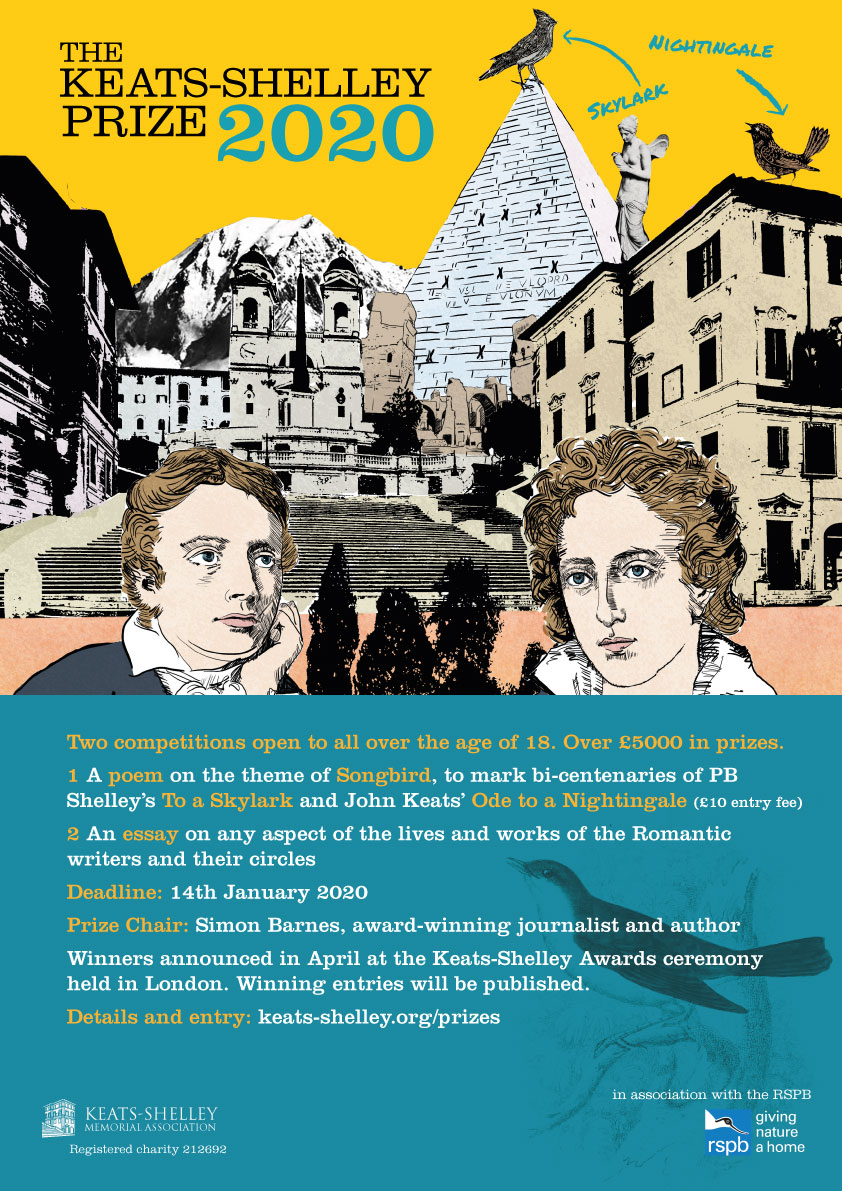

As in previous years there are two competitions - an Essay and Poetry Prize - which are divided into two age groups: the Young Romantics, aged 16-18, and the main Keats-Shelley Prize, which is open to all.

Details of Keats-Shelley Prize are here.

Details of Young Romantics Prize are here.

Both poems have particular resonance for the Keats-Shelley House. Shelley wrote his poem in Livorno, following an evening stroll with his wife Mary, who in 1839 recalled: ‘In the spring we spent a week or two near Leghorn, borrowing the house of some friends, who were absent on a journey to England. It was on a beautiful summer evening while wandering among the lanes, whose myrtle hedges were the bowers of the fireflies, that we heard the caroling of the skylark, which inspired one of the most beautiful of his poems.’

Keats had written his poem in May of the previous year, and in July it appeared in James Elmes’ Annals of the Fine Arts. In 1820, ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ was included in the final poetry volume published during Keats’ short lifetime: Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St Agnes, and Other Poems. ‘To a Skylark’ was also published in 1820, alongside other great lyrics like ‘Ode to the West Wind’, ‘The Cloud’ and ‘Ode to Liberty’ in Prometheus Unbound.

‘Immortal birds…’

Over the next two centuries, the two songbird poems gradually attained classic status. As Alexander Mackie wrote in 1906, ‘The nightingale and the lark for long monopolised poetic idolatry – a privilege they enjoyed solely on account of their pre-eminence as song birds. Keats’ ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ and Shelley’s ‘To a Skylark’ are two of the glories of English literature; but both were written by men who had no claim to special or exact knowledge of ornithology as such.’

Their enduring popularity can be seen in their near omni-presence in Romantic anthologies and polls to favourite poems, and also their pervasive and occasionally surprising influence.

‘To a Skylark’ has inspired writers as diverse as Thomas Hardy and Noel Coward (Blithe Spirit), while Keats’ felicitous phrase-making echoes in works by F Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night and Blur’s song of the same name.

‘And no birds sing’

Reading both poems in 2019, it is impossible not to hear poignant new strains underlying other felicitous phrases: Keats’ ‘Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!’, and Shelley’s ‘The blue deep thou wingest,/And singing still dost soar, and soaring ever singest.’

One unavoidable tragic irony of immortalising the skylark and nightingale in art is the rapidly intensifying threat to both songbirds in reality. In 2015, the skylark and nightingale were both on the Birds of Conservation Concern’s 2015 Red List – which alerts the public to those species currently in most danger of extinction.

The British Trust for Ornithology reports that the United Kingdom’s nightingale population has fallen by 91% over the last 50 years. Skylark numbers halved during the 1990s alone according to the RSPB, and dropped 75% between 1972 and 1996. The causes include everything from changes in farming to urban noise, a rising deer population to climate change.

‘We have to start celebrating these species and the arts are a very important way of brokering awareness and creating an agency for change.’

Sam Lee, folk singer

One of the very few silver linings is the response of artists to the songbird crisis.

The RSPB’s ‘Let Nature Sing’ campaign successfully propelled a recording of songbirds including the nightingale in the top 20.

In May 2019, folk singer Sam Lee and The Nest Collective performed ‘Singing with Nightingales’ at event organised by climate change protestors Extinction Rebellion in London’s Berkeley Square, the setting for the 1939 ballad made famous by Dame Vera Lynn.

The street artist ATM, whose speciality is portraits of endangered bird species in urban spaces, painted a nightingale on the tailgate of a Wellington bomber, an homage to cellist Beatrice Dillon’s annual duet with a nightingale that in spring 1924 became the BBC’s first live to radio broadcast.

Filmmakers Luke Massey and Katie Stacey raised over £10,000 to make The Last Song of the Nightingale, an hour-long documentary celebrating this most iconic of birds while also warning of its precarious future.

Our hope for 2020’s Keats-Shelley Prizes is our poets will draw inspiration from these artists, whose celebrations of art and nature double as warnings about the fragility of the world around us, and our Young Romantic essayists will consider how art can participate in this global wake up call.

To misquote Shelley: ‘The world should listen now, as I was listening then.’

James Kidd