The theme of 2021’s Keats-Shelley and Young Romantics Prizes is ‘Writ in Water’, inspired by John Keats’ epitaph ‘Here lies one whose name was writ in water’.

With the Awards Ceremony imminent (16th September, 7pm GMT), we have gone on a quest to find some of the places ‘Writ in Water’ has founded itself in the 200 years since Keats the words up, with extensive help of course from Shakespeare, Beaumont and Fletcher, John Donne, Catullus to name just five.

Here is our top 11. Please let us know if you spot any others. Email: friends@keats-shelley.org

1. ‘Writ in Water’: the gravestone. It wouldn’t a ‘Writ in Water’ list without this, would it? It took over two years for Keats’ epitaph to be writ in stone, thanks in part to arguments amongst his circle of Friends about what should, and shouldn’t be, inscribed on his grave. Joseph Severn, who recorded the phrase in a letter to Charles Brown on 14th February 1821, was never a fan of Keats’ final message, and lobbied both then and later when the grave was restored to have the 9 words left off.

2. Writ in Water: the trailer. Apologies for the self-promotion: the trailer is for 2021’s Keats-Shelley Prizes. One of the things we have spent a lot of time pondering over the past months is the question: can you write on water? Our attempt to solve the seemingly paradoxical, if not impossible notion was to use a practice employed by Chinese calligraphers, who write in water on specially treated paper. The idea, if we understand it, is to avoid wasting folios of paper while perfecting your art.

We gave it a go when dreaming up a trailer for 2021’s Keats-Shelley Prize: watch below. One of the more Keatsian effects is that the text slowly vanishes before your eyes as the water dries. This version of the trailer is run backwards to lend Keats’ epitaph its more optimistic nuances.

Of course we were far from the first to try and write in water. The Italian artist Guildor gave it a whirl with his inventive floating graffiti art work ‘Write on the Water’.

In the early 2000s, a Japanese company developed AMOEBA, or Advanced Multiple Organized Experimental Basin. Waves are generated by machines underwater to create shapes on the surface. Quite what the everyday use might be beggars the mind, but the video is good fun.

3. Writ in Water: the avant garde musical piece. Steven Brown is the co-founder of avant garde musical duo Tuxedomoon. Brown loves Keats enough to have recorded an entire album, The Day is Gone, interpreting his poems, life and writing. Brown’s renditions of Keats poems like Ever Let the Fancy Roam, You Say You Love and To Hope combines old school spoken word, looped vocals incant particular phrases, music and field recordings.

These is also a trilogy of works entitled ‘Writ in Water’. Listen to Writ in Water 1, which was partly recorded beside Keats’ grave.

You can buy the album via Bandcamp. Highly recommended.

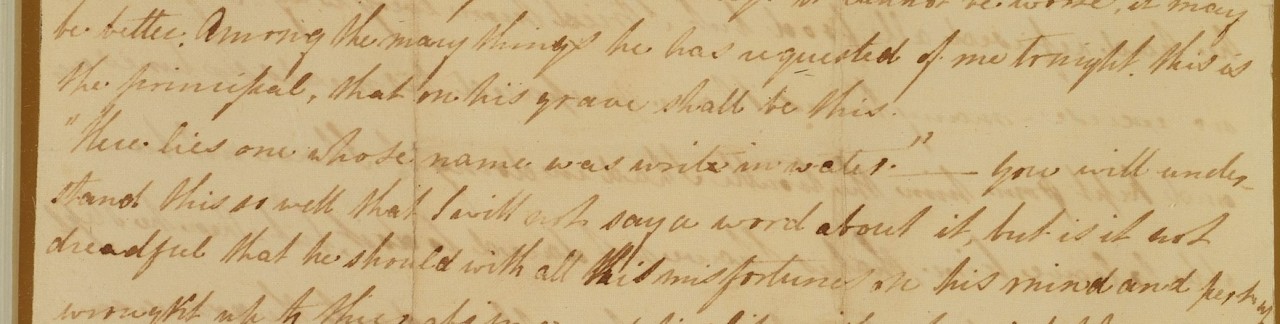

4 Writ in Water: the heartbroken/heartbreaking letter. If the first appearance of Keats’ epitaph in print was in Joseph Severn’s letter to Charles Brown of 14th February 1821, its next may well have been the copy Fanny Brawne made in late March or April of the same year.

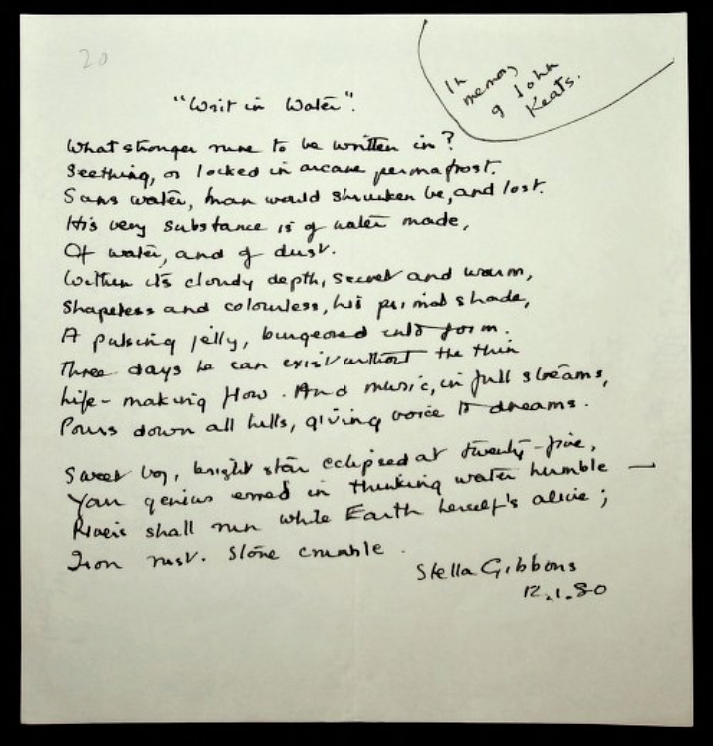

5 Writ in Water: the poem. Stella Gibbons is best known for her comic masterpiece Cold Comfort Farm. But she was also a devoted, if occasional poet: apparently this was her preferred literary job description until the end of her life. She wrote this poem, dedicated to John Keats, on 12th December 1980, when she was 78. Gibbons spent most of her life in and around Hampstead, living for a time in the Vale of Health after her parents died and she was left to raise her siblings.

Gibbons’ manuscript is now in the proud possession of Keats-Shelley House.

Read more about ‘Writ in Water’, and Gibbons’ admiration for Keats, at the Keats-Shelley Blog.

6. Writ in Water: the performance art. ‘Whose Name was Writ in Water’ is a three-part, theatrical performance written and performed by Becci Davis. In the piece, the Georgia-born actor, writer and artist imagines a dialogue with her great-grandmother Charity Ann, a slave bought and sold by the Parker family of the county of Harris in Georgia. For Davis, ‘Whose Name was Writ in Water’ sounds like a question, a statement and a quest to discover her past. As she writes of the piece: ‘Water serves as the device that connects them through time and space while she struggles to undo the effects of a history that cannot be erased.’

Watch Davis talk about her great-grandmother and ‘Whose Name was Writ in Water’.

7. Writ in Water: the ambient cure to insomnia. Max Richter is one of the biggest names in modern classical/electronic music, whether he is writing soundtracks for film and television or producing his own work. In 2015, he released one of his most ambitious projects: Sleep, an 8 hour 30 minute piece of music that both encourages sleep and tries to evoke it too.

Part of this epic, beautiful album is a four-part song-cycle entitled ‘whose name is written in water’, which also features Grace Davidson’s dreamy vocals. Listen below.

8. Writ in Water: the art installation. In 2018, Mark Wallinger unveiled his monumental architectural installation ‘Writ in Water’ to commemorate 800 years of the signing of the Magna Carta in Runnymede.

Learn more about the project here.

Listen to Mark Wallinger talking to the Keats-Shelley Podcast about John Keats, ‘Writ in Water’, art in the time of Covid and whether poets and artists can be friends.

9. Writ in water: the modernist masterpiece. Dutch-American painter Willem de Kooning painted ‘Writ in Water’ in 1975, almost 20 years after Gregory Corso showed him round Rome in 1958, and probably took him on a guided tour to John Keats’ house in Piazza di Spagna and his grave in the Non-Catholic Cemetery. De Kooning fell in love with the city, and returned for a lengthy sojourn a year later, although he spent most of his time drinking and partying.

Keats’ epitaph clearly stuck in de Kooning’s mind. He was 71 years old when he completed ‘Writ in Water’, which Harold Rosenblum the New Yorker’s great art critic described as ‘the closest de Kooning can come to saluting overtly the impermanence of existence, and things in a state of disappearance.’

10. Writ in water: the Moby Dick cameo. Herman Melville visited Rome’s Non-Catholic Cemetery on 27th February 1857. His main reason for a trip that caused ‘much trouble & sore travel without a guide’ was Shelley. Melville’s pilgrimage to the poet’s grave was part of a wider Shelley tour that began with the baths at Caracalla (‘Wonderful. Massive’) and ended with the Cenci Palace.

Melville did however hop over the trench separating Shelley’s tomb from that of Keats. His only comment ‘Read Keats’ epitaph’ is noteworthy. For 6 years earlier, Melville wove the phrase into a later chapter (134) of Moby Dick, in punning conjunction with the word ‘wake’.

Listen to chapter 134 read by Roger Allam as part of Moby Dick: The Big Read.

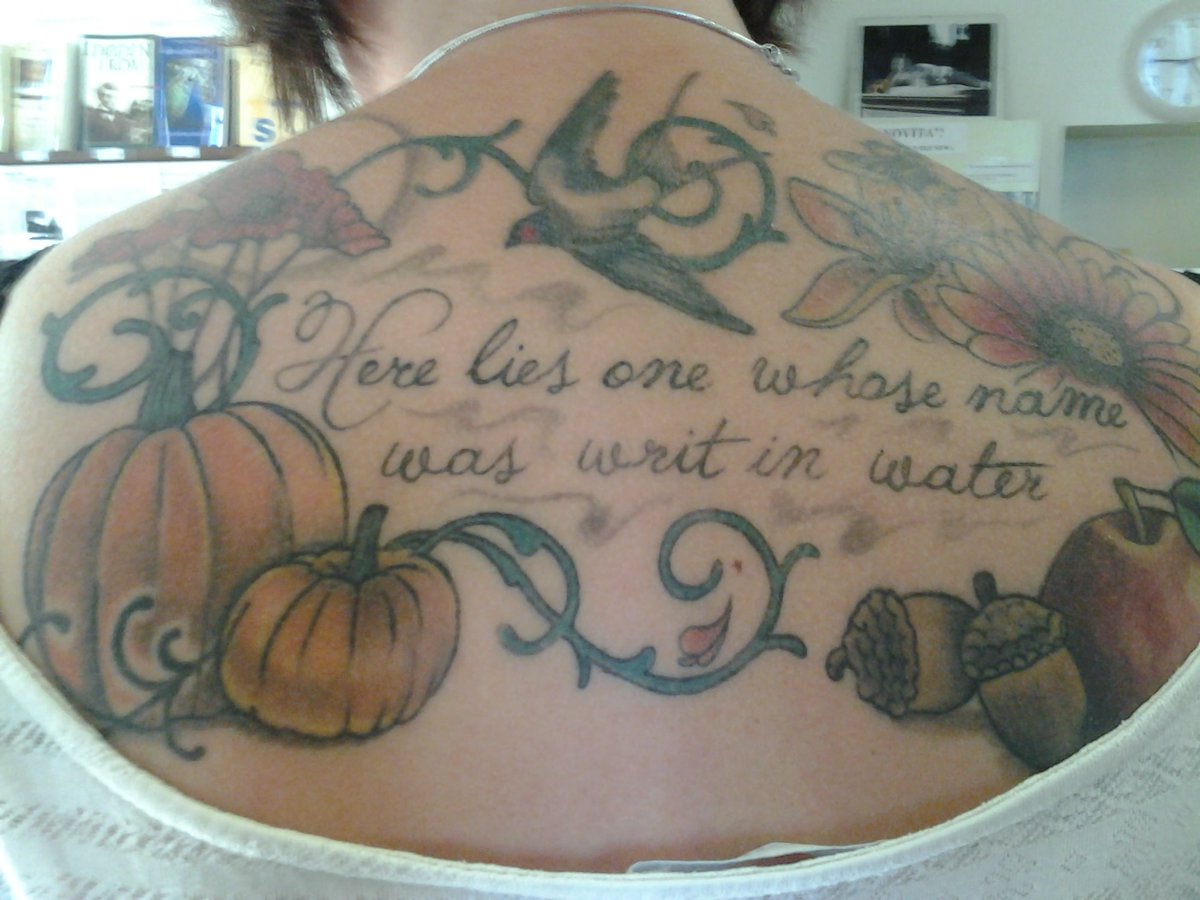

11. Writ in water: the tattoo. We were sent this extraordinary tattoo back in 2016. Perhaps the most committed homage of them all…