Excerpt from Chapter 21 of The Hard Life by Flann O’Brien

- Oh there is one thing I forgot to tell you. On the night before the funeral I got in touch with one of those monumental sculpture fellows and ordered a simple headstone to be ready not later than the following night. I paid handsomely for it and the job was done. It was erected the following morning and I have paid for kerbing to be carried out as soon as the grave settles.

- You certainly think of everything, I said in some admiration.

- Why wouldn’t I think of that? I might never be in Rome again.

- Still….

- I believe you are a bit of a literary man.

- Do you mean the prize I got for my piece about Cardinal Newman?

- Well, that and other things. You have heard of Keats, of course?

- Of course. Ode to a Grecian Urn. Ode to Autumn.

- Exactly. Do you know where he died?

- I don’t. In his bed, I suppose?

- Like Collopy, he died in Rome and he is buried there. I saw his grave. Mick, give us a ball of malt and a bottle of stout. It is beautiful and very well kept.

- That is very interesting.

- He wrote his own epitaph. He had a poor opinion of his standing as a poet and write a sort of jeer at himself on his tomb-stone. Of course it may have been all cod, just looking for praise.

- What’s this the phrase was?

- He wrote: Here lies one whose name is writ on water. Very poetical, ah?

- Yes, I remember it now.

- Wait till I show you. Drink up that, for goodness’ sake! I took a photograph of Collopy’s grave just before I left. Wait till you see now.

He rummaged in his inside pocket and produced his wallet and fished a photograph out of it. He handed it to me proudly. It showed a large plain mortuary slab bearing this inscription:

COLLOPY

Of Dublin

1848-1910

Here lies one whose name

is writ in water

R.I.P.

- Isn’t it good, he chuckled. ‘In water’ instead of ‘on water’?

- Where’s his Christian name? I asked.

- Bedammit but I didn’t know it. Neither did Father Fahrt.

Pages 121-122, in 1978 Picador paperback edition.

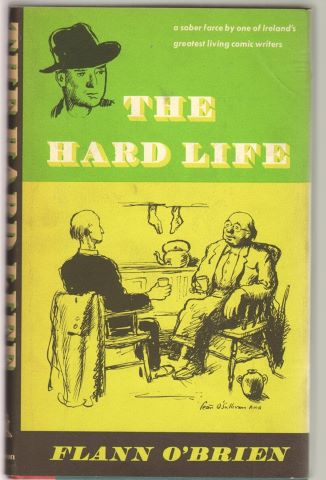

Flann O’Brien is revered as one of the world’s greatest and most inventive comic writers. Nowhere was his invention more, well, inventive than his own name. Flann O’Brien was also aka Brian O’Nolan, to give him his none de plume, and aka Brian Ó Nualláin, as it is writ on his gravestone, and aka Myles na gCopaleen, as he was known to the many readers ‘The Cruiskeen Lawn’, his daily column for the Irish Times which reads as if James Joyce was given a society page. This began life as an informal poetry review. On 29th July 1940, one ‘F. O’Brien’ responded, with semi-serious mockery, to the paper’s publication of Patrick Kavanaugh’s ‘Spraying the Potatoes’:

‘Perhaps the Irish Times, tireless champion of our peasantry, will oblige us with a series in this strain covering such rural complexities as inflamed goat-udders, warble-pocked shorthorn, contagious abortion, non-ovoid oviducts and nervous disorders among the gentlemen who pay the rent.’

This sparked a small avalanche of correspondence taking the sides of the poet and critic respectively – some of which at least were also written by O’Brien under other names. The debate was brought to a close when Kavanaugh himself intervened, gently but firmly to bemoan how alienated his urban critics seemed from the rural visions of his poem: ‘Ploughmen without land,’ he called them. The two writers would become friends, albeit warily.

O’Brien’s five novels (five and half if you count the unfinished Slattery Sago’s Saga) include bona fide classics like At Swim Two Birds and The Third Policeman, and are bolstered by short stories, plays, poems and still more journalism, written in both the Irish and English languages. Of greatest interest to Keats lovers are the squibs starring ‘Keats and Chapman’. Inspired in the loosest sense of the word by John Keats’ sonnet ‘On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer’, O’Brien fused the shaggy dog story and the double act with high-minded classical references, a relish for vernacular and contrived plotlines all of which served the sole purpose of hitting the punchline (usually utterly and exquisitely terrible). To wit:

‘Chapman thought a lot of Keats’s girl, Fanny Brawne, and often said so.

‘Do you know,’ he remarked one day, ‘that girl of yours is a sight for sore eyes.’

‘She stupes to conquer, you mean,’ Keats said.’

While many of the tales exist only in their own highly wrought universe, a few seem to touch however lightly on the actual John Keats.

‘Keats was once presented with an Irish terrier, which he humorously named Byrne. One day the beast strayed from the house and failed to return at night. Everybody was distressed, save Keats himself. He reached reflectively for his violin, a fairly passable timber of the Stradivarius feciture, and was soon at work with chin and jaw.

Chapman, looking in for an after-supper pipe, was astonished at the poet’s composure, and did not hesitate to say so. Keats smiled (in a way that was rather lovely).

‘And why should I not fiddle,’ he asked, ‘while Byrne roams.’’

It is entirely possible that O’Brien produce these miniatures with mischievous intent - to poke fun at one of the apparent grandees of English literature, much as he poked fun at Kavanaugh as a grandee of Irish literature. But nor is it hard to hear affection running throughout the ‘Keats and Chapman’ fizzles, as is suggested by that surprisingly tender notice of Keats’ smile ‘(in a way that was rather lovely)’. Does O’Brien in fact empathise with the excitement Keats felt when Homer, assisted by Chapman, waved him in from his place on the bench to play in the ‘realms of gold’? Stir in Keats’ love of a pun – ‘many a mused rhyme’ – and you might wonder whether the two were soul mates, or at least sole mates.

Similarly hazy, uncertain warmth pervades the ‘Writ in Water’ quoting extract from O’Brien’s late novel The Hard Life (1961), which takes satiric pot-shots at the Catholic Church, Irish politicians, education (in Ireland and England) and universal human folly. Could we add Keats to the list?

- Do you know where he died?

- I don’t. In his bed, I suppose?

Does the laconic punchline laugh at Finbarr’s ignorance, or send up a stuffy presumption of Keats’ fame? Or both?

Almost all the novel’s critiques are embodied by the recently deceased Collopy. Before his frankly bizarre death in Rome (he was given an overdose of a weight-raising medicine called ‘Gravid Water’), Collopy was guardian to Chapter 21’s two orphaned speakers: Finbarr and his brother (known only as ‘the brother’), who spins most of the yarn. Hints are dropped throughout the novel about Collopy’s grand charitable project to reform the lives of Dublin’s women. On his death, Collopy’s mission is revealed as the establishment of decent public female lavatories – which doesn’t sound quite as satirically unreasonable today as it might have done 60 years ago.

In not dissimilar fashion, the jokes on Keats’ epitaph feel in keeping with the playful ambivalence of the ‘Keats and Chapman’ series:

‘- He wrote his own epitaph. He had a poor opinion of his standing as a poet and write a sort of jeer at himself on his tomb-stone. Of course it may have been all cod, just looking for praise.’

O’Brien’s signature bathos could be poking fun at Keats or sharing the fun with him. Read in the context of Collopy’s life’s work, ‘writ in water’ adds non-too-subtle urinose undertones to Keats’ epitaph: Collopy dreamed that his mission for women’s toilets would one day deserve a plaque with his name writ large. But this scatological double entendre may also have been on Keats’ mind too: see this post from our Google Earth map, John Keats’ Final Voyage. Beneath this subtext is another, alluding to his unfortunate death by ‘Gravid Water’. The medicine is one of the novel’s several get-rich-quick schemes (or scams), whose fatal dose, tragically, is administered by Finbarr.

Beneath this (second) subtext lurks yet another. ‘The brother’s’ evident pride in his epitaph derives from in part from the naughty appropriateness of the pun and also the mangling of Keats’ original text: ‘- Isn’t it good, he chuckled. ‘In water’ instead of ‘on water’?’ Only, the joke is also on ‘the brother’. What he considers to be a clever reinvention is in fact a near photocopy: Keats’ epitaph ends with ‘writ in water’ (my italics) in exactly the same way as Collopy’s. In other words, ‘the brother’ has misread the original as ‘writ on water’. Perhaps he is reverse engineering an act of plagiarism as one of creation? Has O’Brien launched a cunning assault on the deification of the posthumous John Keats? Is he providing a sly commentary on originality, influence, memory and artistic re-cycling – such as surrounds Cortez and Darien at the end of ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’? Or is the novel’s slip simply the novelist’s mistake? O’Brien also confuses the tense of the epitaph’s second verb: ‘is writ’ rather than ‘was writ’.

Whatever the answer, I suspect both O’Brien and Keats would simply chuckle at this comedy of errors.

James Kidd

For information about 2021’s Keats-Shelley Poetry and Essays Prizes, whose theme is ‘Writ in Water, click the links below.